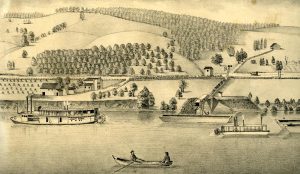

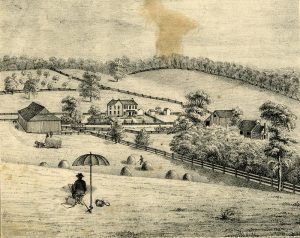

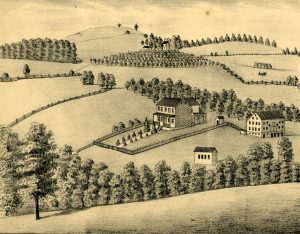

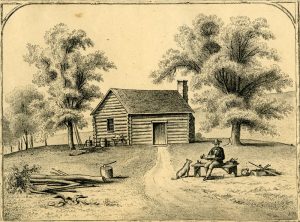

FURROW AND SLICE is a book of short short stories and attending photographs—some of the stories standing on their own, others as chapters of longer works—that portrays the world beyond the valley’s hills of the mill town of Furnass. A world of rolling hills and fields of wheat and oats and corn. A world of isolated farmhouses keeping company only with their barns and outbuildings. A world where the land if left untended goes quickly back to forest where the wild things are. At times the life of the farmlands intersects with the life of the town—at the supermarkets and superstores in the shopping malls, at the shops and restaurants and dealerships along the streets of Furnass. But soon enough the people of the farmlands return home to where they’re known and understood. Proud of who they are, and who they are not.

Furrow and Slice

“A vivid, moving collection that explores the unrecoverable past.” – Kirkus Reviews

Videos

Here’s a video introduction to the mill town of Furnass.

Finding FURROW AND SLICE

When I was in high school in Beaver Falls, PA in the 1950s, a third of the kids were town kids; a third of the kids were suburban kids; and a third of the kids were farm kids. The town kids were the sons and daughters of mill hands and factory workers, along with owners and workers in the town’s stores and services; a third of the third of the town kids were black. The suburban kids were bussed in from Patterson Heights and Patterson Township, areas that covered the top of the valley’s hills above the town, as well as from Chippewa and other areas beyond that were too new to have familiar names; these kids were from upwardly mobile families, or those trying to be, with the nicest clothes, the best grades, and not a black family to be seen. And then there were the farm kids; they were also bussed in though from farther away than the suburban kids, areas like New Galilee and Darlington where the new developments had not yet taken over.

Those fractions, I should note, aren’t entirely accurate—the number of farm kids was probably a small one-third—but it gives you some idea of the general proportions.

The farm kids were pretty much a mystery to the rest of us, what with their blue denim 4-H jackets, worn by both boys and girls, and their clannish nature, all too aware of the difference between themselves and everyone else, though I doubt if anyone could have said exactly what that difference was. The farm kids never participated in the school’s extracurricular activities, such as football or band or drama club, which would have made them seem more “normal,” because they never stayed after classes; we didn’t appreciate that the farm kids had to get home because most of them had chores to do, we thought they were just obsessed with catching their busses to get back to where they came from. I don’t recall anyone ever making fun of the farm kids, though I’m sure some did—“Hey, does somebody smell cow shit in here?” On the other hand, no one ever tried to bully them either, especially not after the time Willi James, a black from the lower end of town and the acknowledged toughest kid in school, had a run in with a farm kid from Enon Valley. Willi had arms the size of some athletes’ thighs, all ripply with muscles and tendons, which he displayed in sleeveless T-shirts; he was also several years older than anyone else in our class because he had flunked a number of times. For whatever reason, Willi crossed paths one day with mild-mannered Jack Wagner, who few people had ever heard say a word one way or the other. It wasn’t pretty. Jack, who after school regularly bucked bales and handled a four-horse team to plough and cut hay, you might say wiped up the floor with Willi. To his credit, Willi was smart enough afterwards to become Jack Wagner’s self-proclaimed best friend, whether Jack acknowledged it or not, and was a vocal defender and advocate for anyone in a 4-H denim jacket.

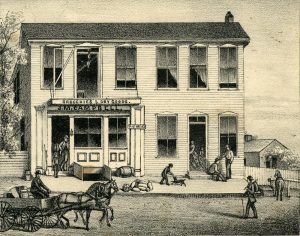

The point is that in a Western Pennsylvania town like Beaver Falls, the mills were center stage, but the farms of the surrounding countryside were off in the wings, always present though not always recognized or acknowledged. I had a friend, Johnny Allen, whose father owned a feedstore on Eighth Avenue behind the main drag; though I knew it was there, and we were often delayed by the freight cars being shunted back and forth and pickup trucks pulling in and out of the loading dock, I never considered or understood what a feed store was or why it might be important, nor cared enough to ask. Likewise, across the bridge to New Brighton there was a feed mill, whatever that was, a stack of metal corrugated structures with a large Purina checkerboard logo on the side of the silo, down the siding from the gas station where I had my first job. Along the main street of town, among the steady parade of tractor-trailers hauling steel and raw materials, there were semis with ventilated trailers full of pigs and cattle and sheep; you learned to quickly roll up your windows whenever one went by. Traveling the back roads out of town, you were often delayed by a line of cars behind a tractor hauling hay bales or manure, another call to roll up the windows. The summer of my senior year in high school Jim Keller had me drive him and a couple of other guys from the College Hill gang (we were the farthest thing from a gang you could imagine) to a farm he knew about out of town beyond Shenango Road; I parked along the berm while they ran giggling into a cornfield in search of watermelons, though the adventure ended abruptly when the dogs starting barking, the lights in the farmhouse came on, and the farmer stood on the porch and fired a shotgun into the air. On the other hand, when my father wanted to relax after a long day in Pittsburgh working with tax codes, he and my mother would take a drive along the windy roads into the farm country beyond the valley’s hills.

After being away for twenty years on the West Coast, when I came back to write about and photograph Western Pennsylvania, the last thing on my mind was farms. My interest was in the obvious drama of the mills and the mill towns clustered around them that had haunted me the years I had been away, the way of life that molded me, the people I first knew and to whom I first learned to relate. My perspective began to broaden, however, after I met the young woman who would become my wife. Marty was born and raised in Hickory, a small farm community twenty miles south and west of Pittsburgh. Marty wasn’t a farm girl per se, though she was born and raised in farm country. Her mother was the second-grade schoolteacher seemingly of every farm kid within a dozen miles—“Good morning, Mrs. Be-ard”—and her father’s most successful venture was artificially inseminating cows and heifers; their house was surrounded with farms, and she and her brother and sister spent most days during the summer on her grandparents’ farm that was just over the hill and down a lane. From the time we started dating, every two or three weeks I would go with Marty down to visit her widowed mother along with her aunt who now ran the family farm. For most of that time I felt no particular interest or affinity for the farm way of life, though I gradually became versant in the terminology and protocols. Among other things I learned that a John Deere tractor was called a Johnny Putt-Putt because that’s the way they sounded when they came over the hill; I also learned that in this particular patch of upper Appalachia, anything with the name of Allis-Chalmers or Ford, much less anything with a Japanese name, was not considered a fit piece of machinery.

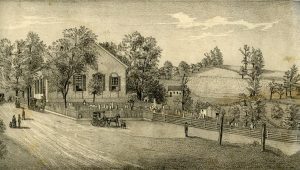

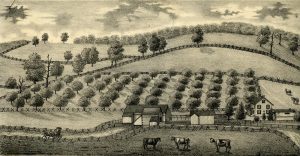

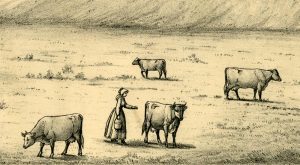

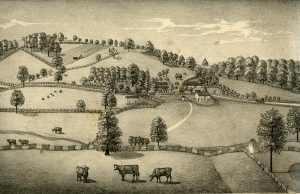

For fifteen years or so, I made the trip with Marty to Hickory without thinking much about it, heading South on 79 then at Bridgeville heading West on Route 50. Beyond the proverbial bumps in the road with names like National Hill and Cuddy, Cecil and Westland Junction, the windy two-lane highway abruptly opened up into rolling countryside as you approached the first of many farms. The curious thing about this first farm was that the road made a large S-curve through the middle of it; you approached the barn on the right, then curved up a steep grade passed the farmhouse on the opposite side, then straightened out again after curving left at the top of the hill. A number of times either coming or going we were stopped by the couple in their mid-forties who owned the farm as they drove their cattle across the road from one field to another or toward the barn for milking. It was a friendly Western Pennsylvania kind-of-thing to wave to the guy, give a little toot of the horn, when we saw him on the tractor plowing or cutting hay. It was always a kick when he waved back.

In the early years of the new century I had started to photograph seriously again, the result of needing to step back from my fiction for a while. And my photographs were getting some recognition. After teaching myself how to use an inkjet printer to make prints that had all the tonalities of the platinum prints I made years earlier, I reprinted all the negatives I had made of mills and mill towns around my hometown in the mid-Seventies while on a grant from LightWorks at the University of Syracuse, a series of prints that were to be shown in a major one-person show at the Heinz History Center. I also had a portfolio of that work accepted by LensWork magazine. Skyhorse Publishing had recently released a book of my photographs and text entitled Kitchen Things: An Album of Vintage Utensils and Farm-Kitchen Recipes. And I had just finished completing a new series of photographs and text of the Flight 93 Temporary Memorial, a series that would be published by Carnegie Mellon University under the title of An Uncommon Field.

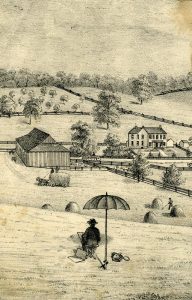

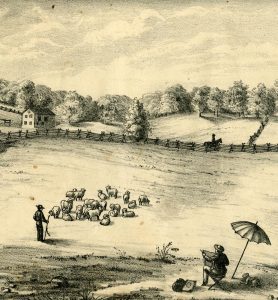

It came as a surprise, though, one day while driving up the hill through the large S-curve that I wanted to photograph that farm. Really wanted to photograph that farm. That I had had the idea in the back of my mind for months, I just hadn’t paid attention to it. There was something about the place that, for lack of a better description, was speaking to me, in the same way that the field near Shanksville where Flight 93 went down—not the spirits of those onboard the plane, the spirits of the place itself—spoke to me. When the desire to photograph the farm kept gnawing at me for a couple of months, I mentioned my interest in the place to Marty’s mom. Well, I should have known. Marty’s mom had the owner of the farm, Chip Cowden, in school—“Good morning, Mrs. Bea-rd”—and one phone call set me up to meet the man. Who would dare refuse Mrs. Beard, even thirty-five years later? As it turned out, Chip and Jo Ann were among the most gracious and supportive and accommodating people I had ever met, and we remain good friends to this day. When I told them my ideal arrangement would be to come to the farm every week or two to photograph the place in all times and weathers, they said I was welcome at any time, no need to check in with them, they’d recognize my truck and gave me permission to go wherever I liked—though they noted it might be a good idea to stay out of any field when the bull was around. I learned later that on several occasions they delayed moving the cows from one field to another or releasing them from the barn after milking because they didn’t want to disturb me where I was working.

For a couple of years I made the trip to the Cowden farm, sometimes dropping off Marty at her mom’s and doubling back, sometimes making the trip there on its own. I regretted that I never photographed the farm in the snow, though frankly I was afraid of getting stuck and having to bother Chip for a tow; and I never photographed it at night, and always wished I had images of the gleaming tanker truck that came in the early hours to take away the milk. Each time I photographed, I would first ask permission of the spirits of the place, and I was always aware of something special going on around me whenever I was there, as if I was simply following some other’s direction or guidance. I think I’ll go over here—no, the image you’re looking for is over there. And sure enough, it would be. Magical thinking, to be sure. In time, though, I wondered about photographing other farms in the area, if I would have similar experiences some place else. Again, a mention to Marty’s mom, and with a few phone calls I had access to close to a dozen nearby farms. The images continued to come, and I met some wonderful people along the way; but whenever I went back to the Cowden farm it felt like going home in some strange way, and the warm greetings weren’t just from Chip and Jo Ann.

Over a period of four years I had approximately one hundred images that I considered worthwhile, and I began the process of making the final prints, using the same printer and inks to produce the tonalities of platinum prints I had used for the mill town series, each image ten inches square on eleven-by-fourteen watercolor paper so the image sank into the paper fibers. The gallery that represented my work, Sewickley Gallery, scheduled a show and I figured that was that, the series for whatever purpose was done. Then an unexpected thing happened. One night after dinner I was looking at the photographs on the computer, the image from the top of a hill looking down at a farm in a shallow valley, when a story occurred to me, the story of two lovers sitting in his car looking down at the farm where she lived with her husband.. Now, for a while I had been I had thinking about short short stories, sometimes called flash fiction (I hate that term, makes them sound like a gimmick). I had long admired Isaac Babel’s collection, Red Cavalry, very short stories about the time he, as a young Jewish journalist rode with the Cossack cavalry of the Red Army during the war with Poland during the Russian revolution— compressed, intense stories that have enchanted me but which I no more understand now than when I first encountered them in my early twenties. With both of my photo-text books, Kitchen Things and An Uncommon Field, I had used a short form for the prose—trying for 300 words per block of text on a page facing each image—and it felt natural to me; I had wondered if it would be equally successful with fiction. And here it was: as I started to write the story to go with the image, the movement and development fell naturally into a 300 word format. Short and sweet, enough to present the characters without telling too much so the image lost its mystery, so the photograph worked not as an illustration but as a metaphor. Then I sat back and marveled at the gift I had just received, aware that I might be on to something special.

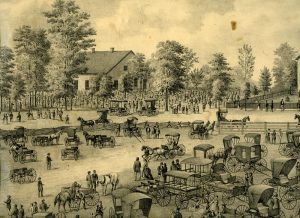

For the next few weeks I would repeat the process, scrolling through the photographs on screen until one grabbed my interest, then study it as a story wound itself around the image. “Farmer’s Market,” “The Web,” “There Goes Love,” “One for Sorrow”—though each required hours of tweaking and rewriting, the stories came pouring out, each a revelation as I discovered these people I didn’t know that I knew.

During this time, Marty’s mom wasn’t doing very well, she was in her mid-eighties, had fallen several times, and required heart valve surgery. One of the things she enjoyed most in recuperating was to go on long drives with us, Marty driving, me in the back seat, traveling the back roads of the area as she and Marty discussed who lived where and when. I don’t recall ever jotting down verbatim someone’s story that they talked about, but hearing the stories of the people of the area and for once being able to just look at the farm country we traveled through brought to mind a continual stream of new story ideas that I would work up in the evenings as I paired them with photographs. With the success I felt I was having with the one photo-one page text format, I began to wonder if it would work with a longer narrative. The only writer-photographer I was aware of who was at all successful with that longer format was Wright Morris, and whether he was successful in The Inhabitants and The Home Place was up for discussion. After several attempts, I decided it only worked, at least for me, if each section of the longer narrative was treated as an individual standalone page, rather than a continuous narrative interspersed with pictures. That helped to make sure that the images complimented the text rather than being defined by it, and vice versa.

I soon realized that what I was doing was adding up to a book. But the final piece of the puzzle didn’t fall into place until I recognized that, although it didn’t look like it at first glance, it was actually another book about Furnass. I couldn’t tell the whole story of the mill town without acknowledging the presence of the farmlands around it, in the same way that I couldn’t appreciate the life of my hometown without recognizing the surrounding farms. The farmlands were always there, the backdrop on which the stories of the mills and mill town were played out. Likewise, I couldn’t tell the stories of the farmlands without the presence of the nearby town, always somewhere present in the thoughts of those who lived there . . . the grocery stores and malls, the hardware stores and dealerships, the hospitals and doctor’s offices, the yellow school buses making their way in the early morning light, the fog resting in the hollows and lying low over the patches of forest, the buses returning again in late afternoons as the shadows lengthen in the fields and between the farm buildings, a woman perhaps pausing on her back stoop as she brings in the washing from drying on the line, an arm raised to shield her eyes, a farmer on his tractor taking notice as he makes one more pass with the cultivator, the rhythms of the engine and the bumps in the furrows as much a part of him as the beat of his heart, children holding hands as they walk along a country lane, avoiding the puddles left from a recent rain where clouds scud across the sky at their feet, each in their own time and in their own way aware of the town beyond the rolling hills, of the smoke and steam rising in the distance from the river valley, the mill town beyond the horizon as if the earth has split open to reveal something essential and irrevocable at its molten core. . . .

Afterward by Brian Taylor

“The soul never thinks without an image.” – Aristotle

As we soon realize when using a camera and a pen, photography and writing are each challenge enough for a lifetime of exploration and expression. In this poetic and powerful collection of photographs and short stories, Richard Snodgrass reveals his mastery of these two forms of “telling.” Both image and text are narratives, yet neither yields nor explains the other; the photographs are not illustrations just as the words are not captions. Each remains independent, as siblings in the same family might tell a story from different vantage points, or the way lyrics intertwine with musical notes to create a song larger than the sum of its parts.

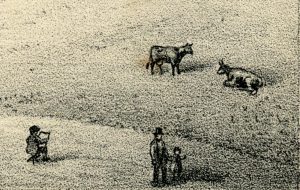

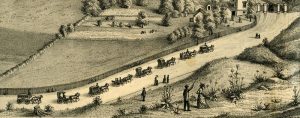

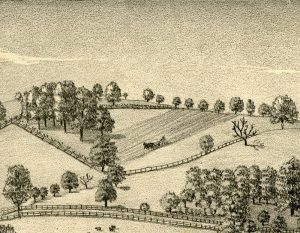

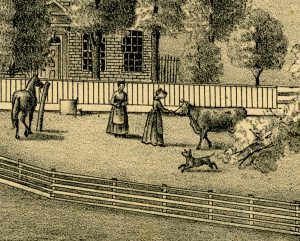

Each story is introduced by a single photograph, gravity-bound in its silent, wordless existence. The scenes portrayed are imbued with a heaviness, laden with the weight of human life and time— time before, during and after the lives of the characters who live and work upon its soil. Lives that will someday be lowered into the earth, joined and forever one with the land. The pictures are beautifully composed, containing subtle textures and intricate tonalities mirroring the shading of the lives described in the stories. The somber earth tones of the photographs are the perfect monochromatic color to represent the measure of hope in the characters’ lives— not resplendent or radiantly colored with opportunity. At times, the images feel like open windows that could be viewed and contemplated by the characters in the stories, carrying and recalling memories from their lives.

The text is visual as well, presenting the wrinkled skin under tired eyes, the folded handkerchief in a farmer’s back pocket, the dirt under fingernails, the patting of a small boy’s head against his will, the eyes of husbands & wives meeting, then quietly looking away. Richly layered with life’s unfolding events, the stories also capture the spaces in between events, words, and conversations. These are the life-changing pauses, quiet and imperceptible, containing unspoken understandings and misunderstandings that profoundly influence and set in motion the remaining course of a lifetime. Snodgrass is a master of such quiet awareness, exploring the silent, liminal spaces between us, moments of waiting, pause and contemplation. As in the beautifully piercing moment of realization in the space within two men’s conversation, “… about this time it must have occurred to Charlie that a smile had a bite to it, like a wolf or a bear about to attack might be thought to smile because it’s teeth were showing.” Or capturing a stunned father’s silent, uncertain thoughts after his son tells him, “Seems to me you always let a lot of things slip through your fingers.”

These short stories reveal the diaphanous interactions between family, friends and neighbors through their challenges of daily existence in this fictional small town of Furnass, PA. These are stories about work and romance, yearning and hope, sadness and endurance, coping and escaping, forbidden yet often consummated temptations. The characters are often restless in their lives, yet lack the awareness or opportunity to change their plight. At times we enter into lives and conversations in an exhilarating midstream journey. We witness the introspection of the characters looking backwards in time and then forward, trying to make sense of an unyielding, often merciless world. There are the somber realizations of a young wife seeing her life laid out before her, knowing that: “… her marriage was never going to be different. That they were going to be just like everybody else.” We are witness to people trapped in the stillness of their rooms: “the house settled around her like a familiar shawl.“ These are moments of quiet resignation we can all relate to: “We are watching our lives play out in front of us.” And later: “… thinking, so this is how it happens. This is when you start to know.“

In stories that unfold indoors, the words and pictures become still lifes of still lives. Snodgrass intricately records the characters’ homes in a powerful documentary style. The photographs are intimate collections of sweaters, bed sheets, pillboxes, recliners, windows and drapes— the actual fabric of people’s lives. These interiors are biographies in plain sight, containing the confessional patina of our valued objects. Snodgrass astutely realizes that still photographs can actually show the passage of time in quiet depictions of teetering piles of newspapers and magazines that reached their heights by slowly rising over weeks, months and years. In a conversation with the author, Snodgrass explained: “If you really want to know somebody, look at the things they think are important and surround themselves with. The things really tell you who they are, what they value. And are immutable testaments of the life they live.”

All of life‘s lessons are here clear and sharp as a surgeon’s knife, the inhalations and realizations between our words and actions. The power of these stories arises from our uneasy recognition that such moments inhabit every day of our own waking lives. In the end, Snodgrass offers us a universality in the fates of these isolated characters, revealing the temptations and possibilities we recognize in our own lives, inviting us to consider the consequences of the yearnings and desires we carry with us on our own journey. And for these considerations let us lead better lives, through a greater awareness of: “ the movement of the planet in its daily round, the lowering of the sunlight at the end of the day setting the late afternoon in deep relief.”

* * *

Brian Taylor was born in Tucson, Arizona. He received his B.A. Degree in Visual Arts from the University of California at San Diego, an M.A. from Stanford University, and his M.F.A. from the University of New Mexico, studying with Van Deren Coke and Beaumont Newhall.

Brian taught as a Professor of Photography at California State University, San Jose for 40 years, served as the Chair of the Department of Art and Art History, and retired as a Professor Emeritus in 2017. Brian also served as the Executive Director of the Center for Photographic Art in Carmel, California from 2015-2019, retiring as Director Emeritus to return to his studio practice.

Reviews, Extra Scenes, etc.

Full Review – IndieReader

IR RATING: 4.8 stars (out of 5)

The dozens of very-short stories in Richard Snodgrass’s collection FURROW AND SLICE depict the intimacies of small town and farm life and the ways in which this lifestyle brings both pride and sorrow, alongside black and white photographs that display the same.

Richard Snodgrass’s illuminating short story collection FURROW AND SLICE pairs photographs with spare prose to show the punitive realities and the pride of small town and farm life. The dozens of black and white photos alternate with very short stories, most as little as one or two pages in length, and feature natural landscapes of farmlands in all the seasons and personal items in peoples’ homes, from chairs and shoes to candles and stacks of papers, all saturated with intimacy and covert meaning, snapshots of peoples’ lives. The stories, too, are snapshots, offering a slice of life perspective of a small town farmers market, the birth of a stillborn calf, a confrontation between an elderly farmer father and a businessman son, and more in which people are tied to the land, to their work, and to each other. In a small space, the writing reveals a great depth of feeling. Gestures as minute as the shrug of a shoulder or the intake of breath are imbued with meaning.

While the writing is beautiful and elegant, many of the stories are too short to be poignant, aiming for insight but just missing; instead of provoking thought, the most successful stories evoke feeling. What does it feel like to want your life to change but to not know how to step out of your comfort zone? How does it feel to see your father watch his wife leave him and carry on with his work as if nothing happened? The characters in these stories, though only in frame for a moment, are fully realized people who wear their histories on their sleeves in the hands of Snodgrass and his sharp, probing prose.

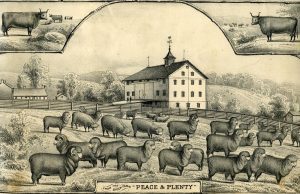

Though the many one-page stories are fleeting glimpses, the longer piece that makes up the last third of the book, “The Hill Wife,” displays the best of Snodgrass’s skill. The perspective expertly shifts from father to son to mother to expose bit by bit, in just a handful of pages, the deepest insecurities, desires, and beliefs of three individuals whose lack of communication has torn them apart. “The Hill Wife,” and most of the other stories in FURROW AND SLICE depict the sort of person who finds a sense of purpose in working the land, tending the flock, doing what has to be done to maintain their livelihood, and finding that it’s enough, even when others can’t understand. FURROW AND SLICE showcases the capacity for concise language to reveal so much in such few words as it puts on exhibit the complexity of farm life without judgement.

Full Review – Kirkus Reviews

A collection of short stories and a novella examine the trials of rural life in a fictional Pennsylvania town.

Snodgrass’ assemblage of fiction, which includes more than three dozen short stories, is set in and around Furnass, Pennsylvania, an old mill town straining under the pressure of modern capitalism and its relentless spread. The prolific construction of McMansions is like a death toll for the area’s vanishing farms, which seem terminally incapable of keeping pace with the times. One of the abiding themes is the disappearance not only of farms, but also legacies—fathers lament the unwillingness of their sons to take over lands they can no longer maintain. For example, in the collection’s novella, The Hill Wife, Noah, an octogenarian farmer, struggles to make ends meet. He wonders if his son, William, a successful real estate agent, pines for his father’s death so he can sell the land. The author presents a typically sensitive and nuanced portrayal of Noah’s tug of war between pride in his son’s accomplishments and resentment at his cold profiteering. In “The Easy Part,” a farmer named Clay is pressured to sell his property, but he clings to the land that has been in his family for eight generations. The short tales are typically very brief, some only a page or two, giving them an impressionistic character, quick snapshots of lives suggestive of backstories never fully revealed. A black-and-white photograph by the author accompanies each tale, highlighting the fiction’s ambient forlornness—a sad nostalgia for a culture that is disappearing not slowly but assuredly.

Snodgrass is at his best establishing an atmosphere of quiet desperation—many of his protagonists, like Clay, know that they can’t win but cling nevertheless to their rapidly displaced ways of life and the inheritances from their ancestors. This stubborn refusal to go quietly can take the form of a defiant, if feckless, pride or materialize as shame. In“An Annunciation,” BJ walks into a clinic in her “brown plaid Walmart five-dollar special jacket” only to be confronted by better-heeled patients. She worries that she’s quickly pegged as “white trash.” The author also unflinchingly tackles the suddenness and inevitability of death and the “endless guilts” of infidelity. Snodgrass artfully contrives an entire literary cosmos, a fossilizing fictional world that faces extinction. But that thick air of lament can be oppressively lugubrious—this is a leaden universe without wit or levity, and the ponderousness can be suffocating. Some of the stories seem to be straining to impart a lesson or function like a moral parable, resulting in a tincture of didacticism. In these tales, treacly sentimentality rears its head. In “Be Still My Heart,” Mary Beth is forced to witness the death of her loved ones repeatedly, a curse of longevity. Her sorrow, though, comes across as canned: “ ‘I had desires too,’ she said out loud, shouted down the hallway. ‘I wanted things too. I’m more than just another fancy plate hanging on the wall. More than just a figurine on a shelf. More than something to put in a stack with all the other stuff you’ve used up but keep around just so nobody else can have it.’ ” Nonetheless, this is a thoughtful compilation, poetically meticulous and often touching.

A vivid, moving collection that explores the unrecoverable past.

A Farm Family Album

Background Material

The following is a selection of the research material I gathered as I worked on the photographs and stories of Furrow and Slice. Highlighted passages are mine.