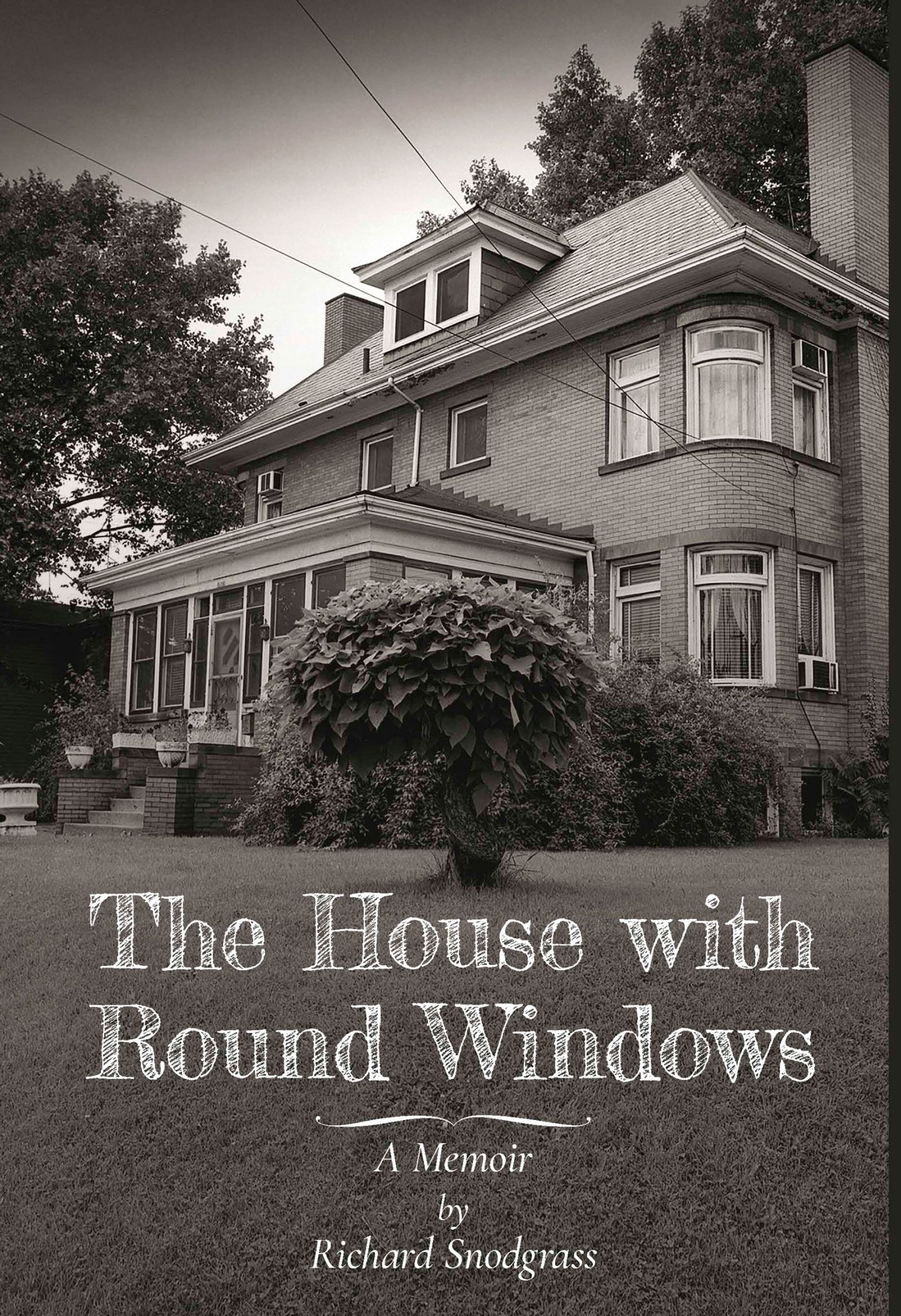

The House with Round Windows — A Memoir

By Richard Snodgrass

The poems of W. D. Snodgrass, based on aesthetics derived from his reaction to events of his troubled family—particularly the death of a beloved sister—directly influenced Robert Lowell, Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath, and changed the course of mid-Twentieth Century American poetry. Now his younger brother, Richard Snodgrass, who actually experienced those family events, masterfully weaves a counterpoint of personal stories, family history and snapshots, and his own photographs into a reminder that there are many sides to any story, that every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way, and—perhaps most terrible of all—that everyone has their reasons.

“Brother of the confessional poet W. D. Snodgrass, Richard Snodgrass portrays his own, differing experiences of their family via photographs and essays that mete out their dysfunction in a chiaroscuro of poignancy and compassion.”

– FOREWARD Reviews, January/February 2022

“The House with Round Windows is a book of interiors. The writer/ photographer Richard Snodgrass recreates the people and accumulation of objects among which he and his brother, the poet W.D. Snodgrass, managed to grew to manhood. Words and pictures take us into a sometimes weird, funny and mysteriously beautiful world of error, sadness, recrimination and the hint of forgiveness. “

– Lore Segal, author of Other People’s Houses; Shakespeare’s Kitchen

REVIEWS, EXTRAS, ETC.

Excerpt from The House with Round Windows

For a while, I considered De the main reason for these visits home. I had the idea to photograph the house to illustrate its relationship to my brother’s poetry. In fact, De never lived in the house for any length of time. A few years at the end of high school; later, for a year or so after he came back from the Navy. But in the poetry of W. D. Snodgrass, the house became the embodiment of all he deplored and condemned about his family, and the world in general—the root of his ethics and his poetics.

His first book, the Pulitzer Prize–winning Heart’s Needle, introduced the family and the house in the very first poem and established the themes that followed throughout the book and, for that matter, the rest of his work: the unquenchable desire for—and the unspeakable deadliness of—love. In Remains, written under the pseudonym S. S. Gardons, the house became the embodiment of a family’s decay and smother love. Later, that oppression became the father figure of Hitler in The Fuehrer Bunker, driving the inhabitants to extremes of behavior, destroying themselves and those around them. The betrayal of loved ones cavorted through W. D.’s Midnight Carnival. He spent decades writing poems in an adapted nursery-rhyme style about the buried terrors of childhood.

My brother’s early work started what came to be known as the Confessional school of poetry—highly autobiographical examinations of self, in plain language, that had a kind of confessional air, an opening up of secrets that paid homage to and sought redemption from the god of psychotherapy. In time, others became more famous at it; others perhaps had a broader scope—Robert Lowell in Life Studies, Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath—but no one else reached W. D.’s heights of lyricism and poetic form. Or, for that matter, his depths of insights into the self’s darker, baser motives. In his later work, he worked hard to wrench himself free of the confessional label, to broaden his range with larger, even historical subjects. But his basic ideas just wouldn’t go away. Underlying all was the thought that sanctuary of any sort, whether it’s home or family, bunker or farmhouse, is a scary place.

In photographing the house, I hoped to reveal something of my brother’s torment and intent. At one time it seemed worthwhile, even an important thing to do. But now I wasn’t so sure. After working on the project for a couple of years, the series had grown into something more. Something different. The experience of exploring the imagery of the house had proven to be an object lesson of its own; though the premises were often the same as in my brother’s work, I sometimes came to different conclusions. As a result, my brother and I disagreed increasingly about the family over the last few years. The latest disagreement, a few months earlier during a visit to his home in Erieville, New York, had sent my brother storming out of his own house in a blind fury, howling into the woods. I was learning that for De the family was a subject you could talk about but not discuss.

All things considered, there seems enough lunacy in the house to go around. Downstairs, on the second floor, I can hear Mother moving about, on the pretense of looking for something, waiting for me to come down. Degas said the dancer is just the pretext for painting. Maybe my desire to photograph the house is nothing more than my desire to photograph. An occasion to make images. To be sure, the rooms are awash with imagery, changing daily like flotsam and jetsam cast ashore on a deserted beach as the old woman, my mother, moves things about.

Reviews:

Foreword Reviews

“Thomas Wolfe was wrong, of course. The melancholy truth is you can go home again,” writes Richard Snodgrass in his memoir The House with Round Windows. Brother of the confessional poet W. D. Snodgrass, Snodgrass portrays his own, differing experiences of their family via photographs and essays that mete out their dysfunction in a chiaroscuro of poignancy and compassion.

Snodgrass was the youngest of the family, born when his parents were almost forty, successful, and buying their first home—a grand, orange-brick edifice in Pennsylvania originally destined to be a lawyer’s clubhouse. He grew up in the shadow of his brother’s poems. And as his older siblings left for the wider world, died, and married, the house filled with clutter, debris, and his parents’ smothering affection, wherein dependency and weakness were proof of love.

While, in Snodgrass’s formative years, he struggled to find his own direction, his latter years became a wrestling match with recurrent “feelings of being a thirty-five-year-old child,” and the “old sorriness and guilt of wanting a life of my own making.” His book doesn’t shy away from the household’s craziness, but—rather than drawing conclusions—it does rely on imagery to speak for itself. Hovering between sketches of emotional confusion and love as a type of stigmata is an awareness that each of his parents was trying to say, “I hurt. Please love me … And the further realization that there was nothing [he] could do to help them.”

Once, Snodgrass “hoped to reveal something of [his] brother’s torment and intent” by photographing the house, but his documentary process revealed the most about himself. Succinct and poignant, The House with Round Windows is a memoir that packs an emotional and visual punch as it peeps into “the Brothers Snodgrass’s” family world.

– LETITIA MONTGOMERY-RODGERS (January / February 2022)

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.

Galleries

The House as it was Then – Photographs by Richard Snodgrass, 1971 — 1976

The photographs in this gallery were taken during the years 1972 — 1976 as described in the book The House with Round Windows. The original photographs are approximately 10” x10” carbon-pigment images, printed on 13” x 17” archival Somerset Velvet Enhanced Watercolor Paper.

The House as it is now

In 1986[?] after the death of her grandmother, my niece Barbara bought the family home. Since that time, she has worked to restore the house to its original condition as well as create a welcoming environment for her siblings and their children. Despite its perhaps troubled past, the house today is smiling, a happy place. The following is a sampling of the photographs Barbara has taken of the house including the work she’s done in refinishing, etc.