The Books of Furnass

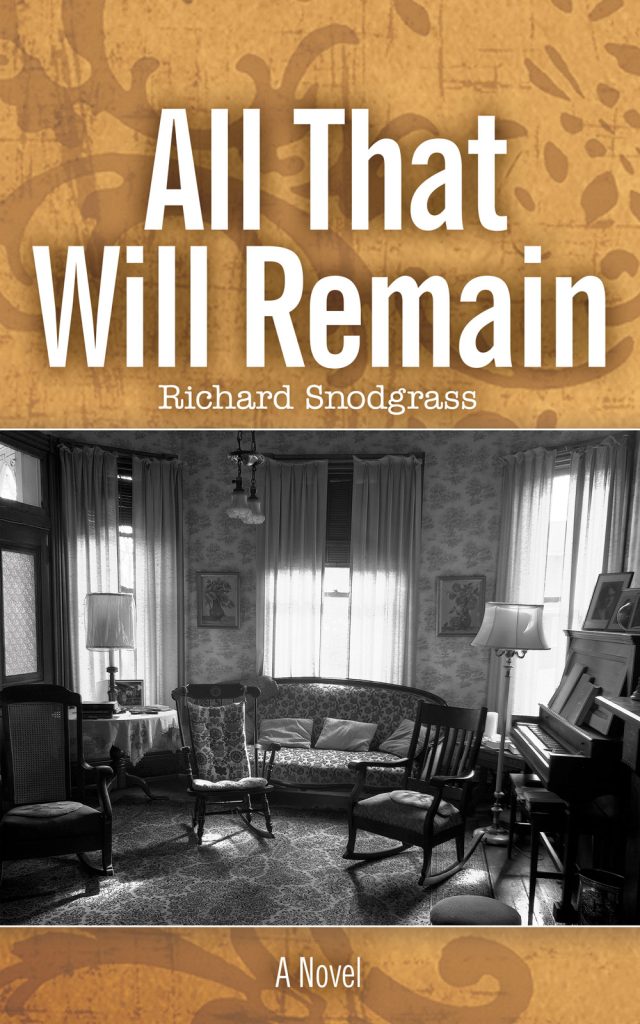

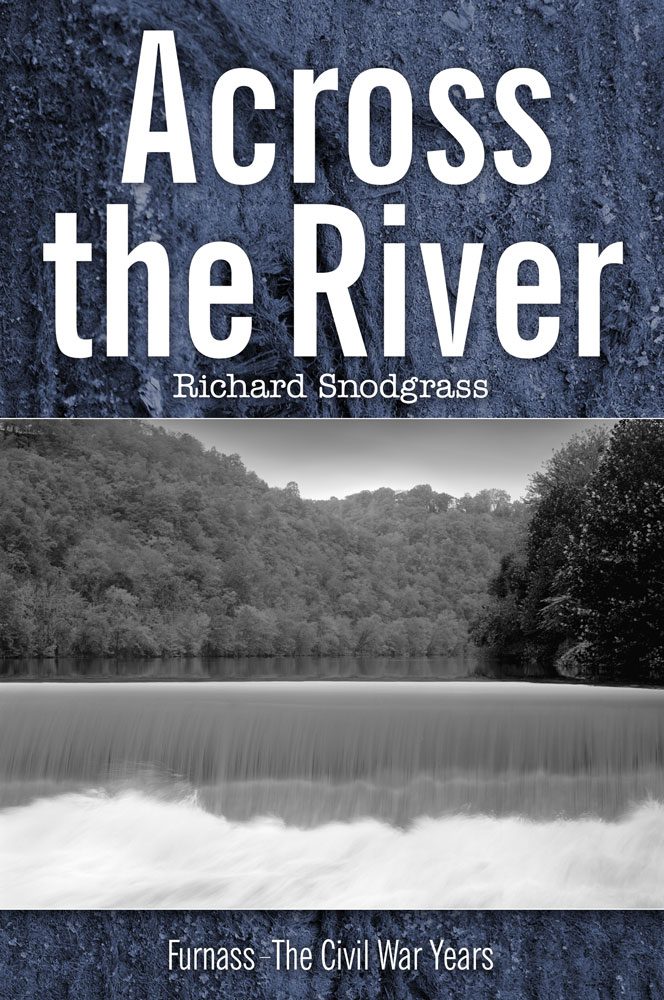

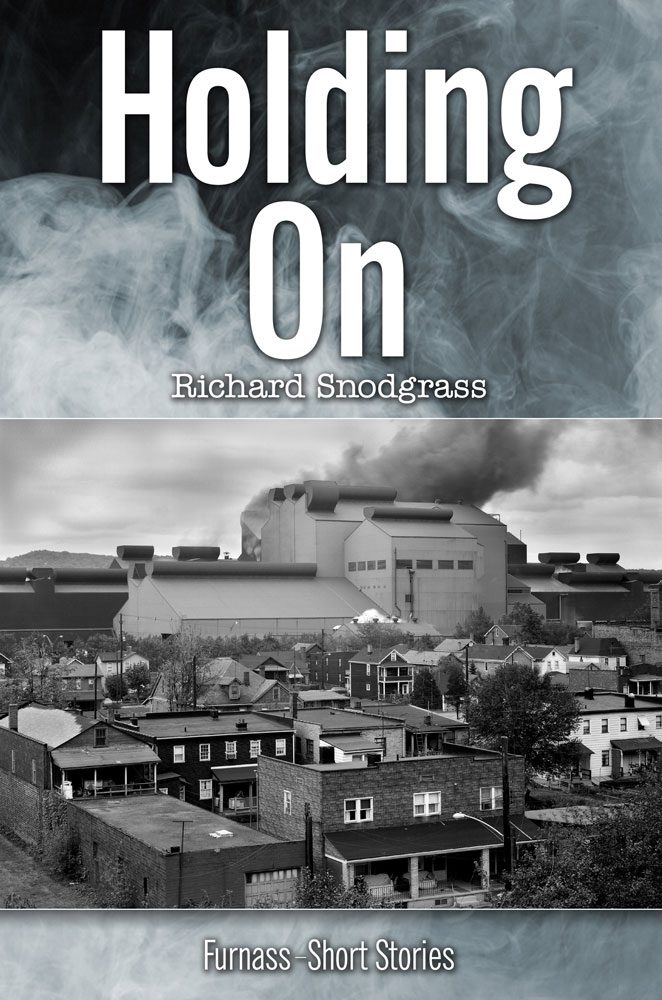

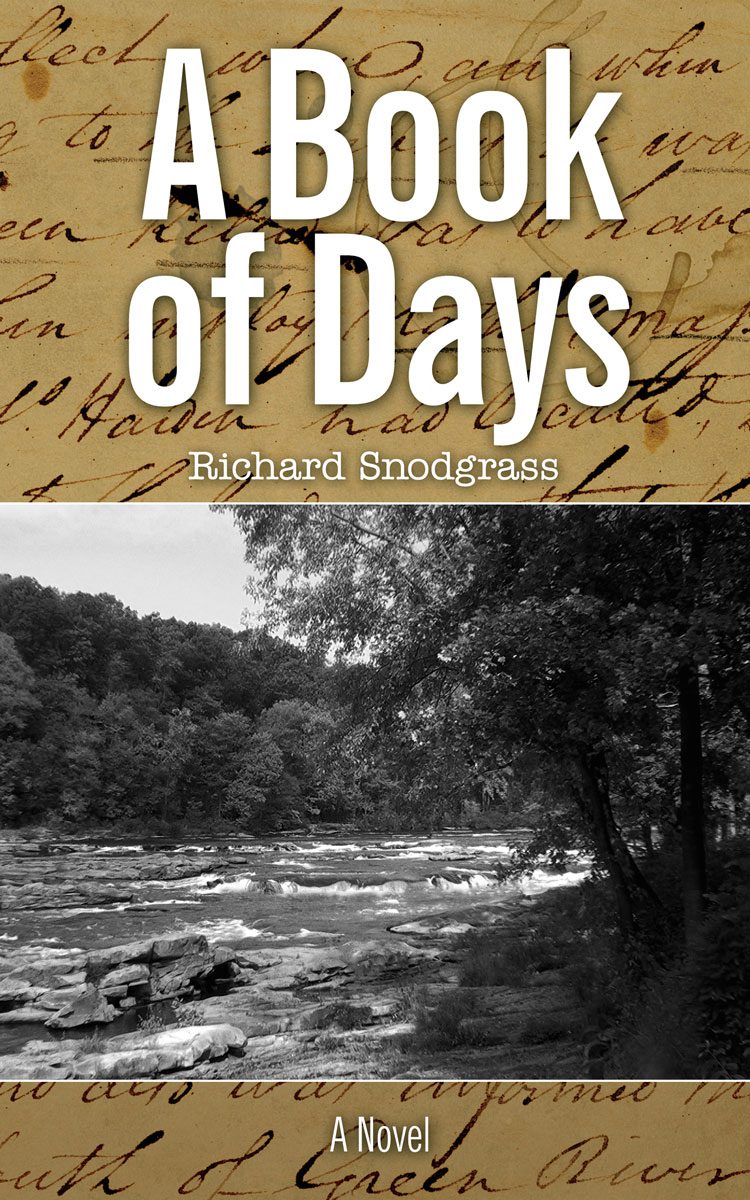

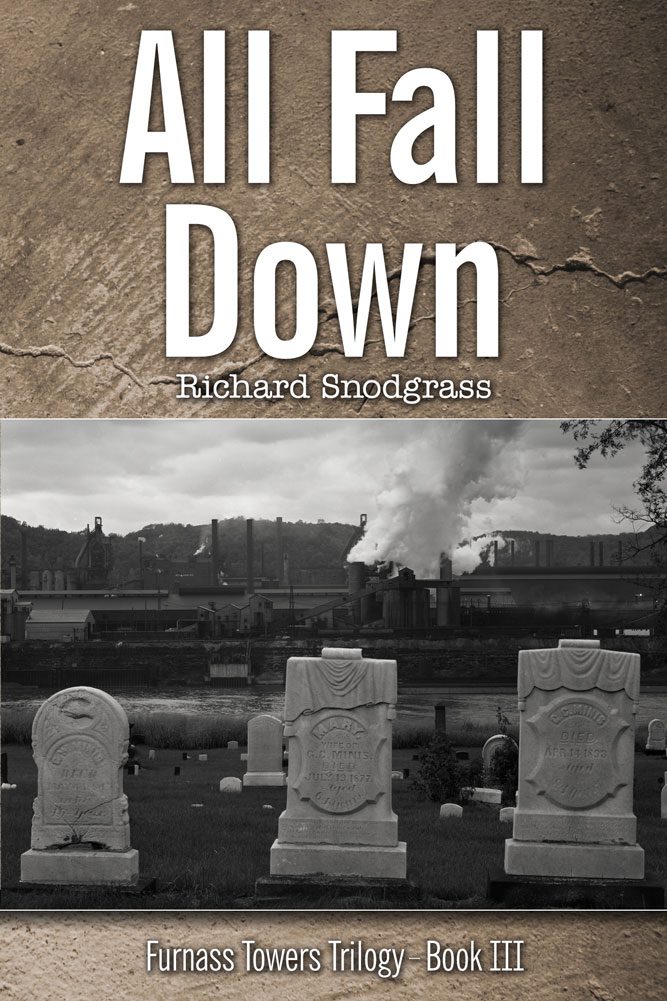

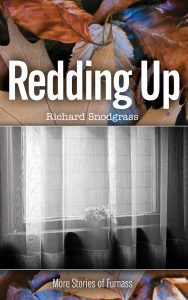

The Furnass Series by Richard Snodgrass consists of eight books to be released one every three months beginning in April 2018. Available both as e-books and in print. For more information about individual titles, click on the highlighted book covers below.

Watch Videos

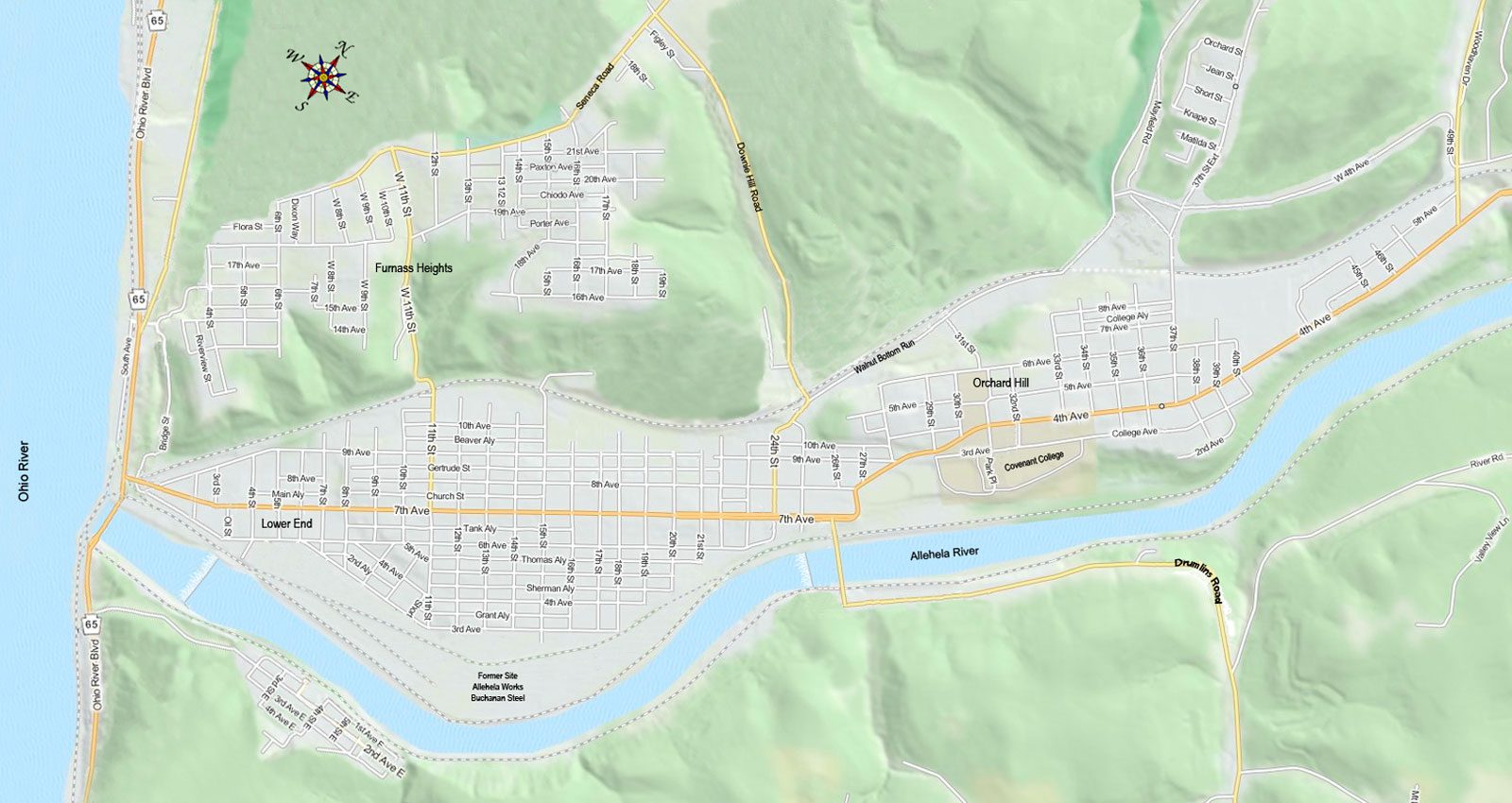

It is a small town, a mill town, a town in a bend in a river, ten miles or so up the Ohio River from Pittsburgh—though not on the Ohio, Furnass is on the Allehela River, close to where the Allehela flows into the Ohio….

It is a small town, a mill town, a town in a bend in a river, ten miles or so up the Ohio River from Pittsburgh—though not on the Ohio, Furnass is on the Allehela River, close to where the Allehela flows into the Ohio….

It is a town squeezed in between the hills and the river, a valley town like other towns in the region squeezed close to their own rivers, towns with names like Ambridge and Aliquippa, Clairton and Donora, Monaca and Beaver Falls…

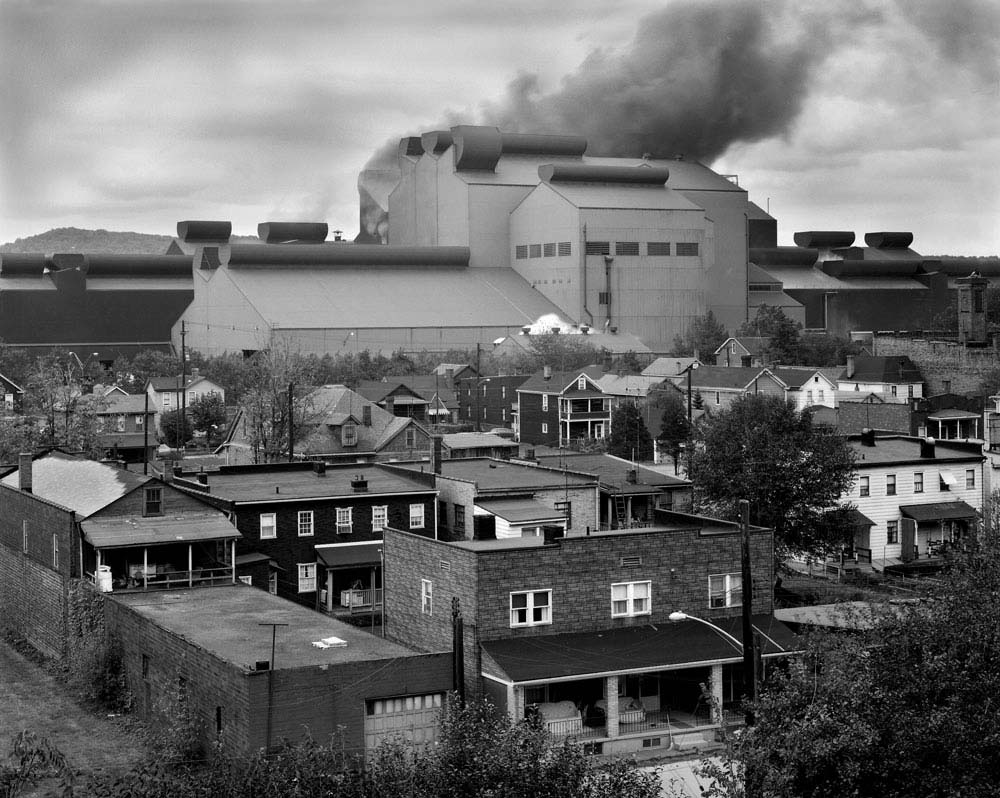

It is a steel town, a town built around a steel mill, in this case the Allehela Works of Buchanan Steel, the mill or mills being the reason for the town, or was at one time, now the mills are gone from Furnass, as they are gone now from most of the other valley towns around Pittsburgh, the glory days of the American steel industry long gone…

It is a town whose reason to be was iron and steel, beginning as a few shacks and cabins around an iron furnace built close to the river in the late 1700s, on the edge of the wilderness that was then Western Pennsylvania, a patch of land that had once been the site of a blockhouse at the end of the French and Indian War and later a small farm before iron ore and limestone were found nearby and a young entrepreneur named Malcolm Lyle with his friend James Buchanan built the furnace from field stone and a town was born….

It is a town that grew as the mills grew. The first settlers were Scots and the Scotch-Irish, those clannish, irascible, tightly wound folks who gave us The American Revolution, The Whiskey Rebellion, and the undying sense of dread that somebody some place is having too much fun, followed later by the English, Germans, and Dutch. When the growing mills required more unskilled labor in the mid-1800s, there was an influx of Irish and Blacks; at the end of the century, the strong backs were provided by Italians, Polish, and Slavs. As each successive ethnic group arrived, they found themselves on the bottom of the social ladder, in Furnass as in American society in general. In time, as the next group arrived, the previous group on the lower rung had the satisfaction of feeling better than somebody. All except the Blacks, that is, who might have been tolerated and even at times appreciated but never assimilated. Part of the town but always kept apart.

It is a town that grew as the mills grew. The first settlers were Scots and the Scotch-Irish, those clannish, irascible, tightly wound folks who gave us The American Revolution, The Whiskey Rebellion, and the undying sense of dread that somebody some place is having too much fun, followed later by the English, Germans, and Dutch. When the growing mills required more unskilled labor in the mid-1800s, there was an influx of Irish and Blacks; at the end of the century, the strong backs were provided by Italians, Polish, and Slavs. As each successive ethnic group arrived, they found themselves on the bottom of the social ladder, in Furnass as in American society in general. In time, as the next group arrived, the previous group on the lower rung had the satisfaction of feeling better than somebody. All except the Blacks, that is, who might have been tolerated and even at times appreciated but never assimilated. Part of the town but always kept apart.

It is a town in three steps along the river. There’s the Lower End, a wedge of flatland crowded with machine shops and warehouses along with a scattering of houses and an occasional bar; the next step up is the main part of town, the business district along Seventh Avenue—the part of town referred to when people said they were headed upstreet or downtown, pronounced in the dialect of Western Pennsylvania, dahntahn—with narrow streets of narrow frame and insulbrick-covered houses backed up the slope of the valley or tiered down to the mill along the river; then there’s the final step up, up Orchard Avenue to Orchard Hill, with Covenant College and tree-lined streets and tidy brick homes tidy lawns, considered the better place to live in town. Of course, if you were really successful or monied you lived above the town along the ridgeline in Furnass Heights or in the suburbs in the rolling hills beyond, but no one considers them part of the town, that being the point of living there.

It is a town whose population remained steady at around twenty thousand through three-quarters of the Twentieth Century. Then the mills began to close in the early 1980s. In the beginning, they were called “idlings.” First the rod and wire mills were permanently shutdown—the blame was placed on imports. In rapid succession two of the three blast furnaces were taken off line, then the seamless tube plant closed followed by the 44-inch hot strip mill and the welded tube mill. The basic oxygen furnace; the continuous caster; the blooming mill. All gone. More than 125,000 manufacturing jobs disappeared from Western Pennsylvania in the space of a few years. In Furnass, it took only two years for the Allehela Works to be shut down completely, its buildings empty husks rusting along the river.

How did it happen? There had been layoffs before, tough times before. People in the mill towns prided themselves in surviving tough times. In surviving. Give it time, they said. Steel will come back. Steel was too big to go away. The mills were a way of life. A way of life couldn’t go away. Management blamed Labor, and, in turn, Labor blamed Management. Both were right, of course, but there were other forces at work as well. The world-wide recession of 1981-82; the growth of foreign steel; the increased use of plastics, aluminum, and ceramics in consumer goods; the rise of efficient high-volume mini-mills—all contributed to the decline of the American steel industry. Then there was the propensity of corporations to please stockholders with the quick and easy profits of mergers and acquisitions.

How did it happen? There had been layoffs before, tough times before. People in the mill towns prided themselves in surviving tough times. In surviving. Give it time, they said. Steel will come back. Steel was too big to go away. The mills were a way of life. A way of life couldn’t go away. Management blamed Labor, and, in turn, Labor blamed Management. Both were right, of course, but there were other forces at work as well. The world-wide recession of 1981-82; the growth of foreign steel; the increased use of plastics, aluminum, and ceramics in consumer goods; the rise of efficient high-volume mini-mills—all contributed to the decline of the American steel industry. Then there was the propensity of corporations to please stockholders with the quick and easy profits of mergers and acquisitions.

Pitted against the arrogance of Management—the subconscious attitude that if you weren’t Management you were in some degree a peasant and could be treated as such—was Labor’s stubborn peasant-nature. The one hope to save the mills and the industry in general involved wage-cuts and production assurances. But when the mills put the problems to the rank and file, the old distrusts and hostilities kicked in. In the words of Joseph Odorcich, Vice President of the United Steelworkers of America, “One of the problems in the mills is that no union man would trust any of the companies. To the average union man, they’re always crying wolf. And the wolf finally came.”

It is a town where, when Love-of-Place met the hard realities of Earning-a-Living, people did the same thing that brought them here in the first place: they migrated someplace else. During the 1980s, the Pittsburgh region lost more than fifty thousand people each year. Fifty thousand people a year. In the town of Furnass, the population drained away quickly from twenty thousand to half that. Those who remained, not counting the elderly or the damaged, the permanently unemployed or the unemployable, might be considered survivors, but they didn’t feel that way. They felt they were home.

It is a typical Western Pennsylvania mill town—except that it exists only in the Furnass books of Richard Snodgrass. Discover Furnass for yourself in the pages of this website.

How Furnass Got Its Name

Furnass

By the time someone came along who cared about the misspelling, a settlement had grown up around the iron plantation, and people were used to the name. So, Furnass stuck.

In Search of Furnass

CLICK THE IMAGE TO VIEW GALLERY

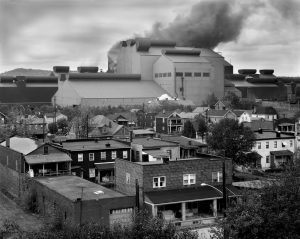

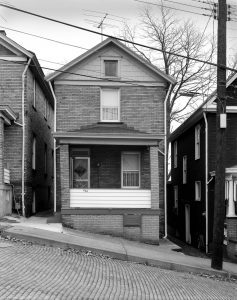

As I wandered through the streets of the valley mill towns, my Deardorff 4×5 camera and tripod slung over my shoulder, I thought that in a way I was constructing my own mill town, or rather, my idea of a mill town, a composite taken from all the mill towns in the area—the most representative Murphy’s 5 & 10; the best view of the mills; the most typical of the little frame houses. I began to call my imaginary town Iron City, in honor of the popular local beer. In time, when I began to write novels about my fictitious mill town, I realized that the photographs grouped together formed the image of Furnass.

The series of photographs, under the title of AfterImage: Mill Life Remembered, was exhibited at the Heinz Regional History Museum, an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institute, in Pittsburgh, PA from September 2005 to May 2006. A selection of the photographs, along with examples of the text I wrote, appeared in LensWork #62, Jan-Feb 2006. Portions of the text were written and researched as part of a grant from the Pennsylvania Council of the Arts.

The photographs and text, a personal history of the steel industry in the Pittsburgh region, along with the experience of photographing the towns after being away for 20 years, are collected in the book When There Was Steel, to be published by Calling Crow Press in 2019.