The Building is the story of the men and women involved with the construction of an ill-conceived apartment tower with insufficient funding in the middle of a dying mill town…the story of a head-strong superintendent who pours concrete when he’s told not to…of a rebar foreman whose insecurities make him dangerous to everyone around him…it is the story of an architect who hides the project’s true cost so he can build a monument to himself…of a young inspector totally out of his depth…and a local developer content to wait and pick up the pieces when the dust settles…and it is the story of a young woman across the alley who dances each morning in her window as she takes her shower, who distracts one worker to the point of a fatal accident and provides sanctuary for another.

Videos

About Book One

Praise for The Building

“This is a sinewy first installment in a planned trilogy—artistically unflinching and morally unsentimental. An audacious, gripping, and wise novel.”

— Kirkus Reviews

“The prose is poetically ambitious and sometimes wildly unrestrained, which is well-suited to the pervasive sense of chaos and urgency…. The pace is unhurried but inexorable, a relentless march toward a shocking conclusion.”

— Kirkus Reviews

“Though on the surface it’s a novel about a single building in a small town, the novel has a big story to tell within an inventive literary framework, making The Building an ambitious and intricately woven work of literary fiction.”

— Self-Publishing Review

“Snodgrass does not fall victim to stereotypical portrayals of women – she [Pamela] has depth and carries herself through her narrative in such a way that makes the reader sad to say goodbye.”

— Self-Publishing Review

“Like the Mississippi William Faulkner evoked in his Yoknapatawpha County novels, Furnass commemorates a slice of the Rust Belt as a singular place and time of sadness yet endurance. The construction industry seldom is the topic of serious literature, but in The Building it rises to great heights, a distinctly American tragedy.”

— IndieReader

5 Star — “IndieReader Approved”

For full reviews of THE BUILDING, see “Reviews, Extras, Etc.” on this page, or click here.

Reader’s Guide to THE BUILDING

Summary

The action in The Building unfolds over the course of a single day, a spring Friday, in a small town in the hills of western Pennsylvania, on a construction site where a new high-rise is being built. Starting early in the morning, when the field supervisor tells the jobsite superintendent not to pour the concrete for the columns—and the manager goes ahead and does it anyway—things don’t go as planned. Missteps affect everyone from a welder to the inspector to the developer to the architect to the waitress in a nearby diner, but they especially affect the rebar foreman and the construction superintendent himself, whose mutual feelings for the woman living across from the site reach a crisis point, with tragic consequences. The Building, a deliciously dark yet ultimately hopeful novel, takes us behind the scenes into an often closed society that few have entered. It also reminds us that dangerous work should be done only with people you trust. Above all, The Building is a story about the triumph of love—the love between a man and a woman, the comradeship and camaraderie that develop between coworkers, and the profound dedication a worker brings to his craft.

Questions and Topics for Discussion

- The Building gives readers a glimpse of the behind-the-scenes mechanics and the many details involved in the construction of a high-rise building. Does this insight affect the way you think about or look at high rises in your own neighborhood or vicinity?

- Who is at fault for the accident at the construction site? If more than one character is responsible, is any particular character more at fault than another?

- Each of the characters has evolved his or her own way of adjusting to the hardships of life—of getting through the inevitable disappointments of each day without losing sight of the joys life also has to offer. What does each character share in this effort? And in what ways do their efforts differ?

- The Building is the first in a series of books set in the fictional town of Furnass, a place that, like Thomas Hardy’s Wessex and William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, has its own unique characteristics and group of inhabitants. What distinguishes Furnass from its literary predecessors? What does it have in common with them?

- What is the role of the book’s italicized passages, written from the point of view of an omniscient narrator? What other books or works of literature intersperse such a viewpoint with those of various characters?

- At one point in the book, Jack says, “You’re really lucky at the end of your life if you’ve got six friends. I don’t mean people you know, I mean real friends, people you can really count on. You’re lucky if you’ve got enough friends to count on the fingers of one hand.” Do you agree with this statement? Does it mirror your own experience?

- What did Gregg learn about himself from his stint as a construction inspector? If he decides to pursue it as a career, will he be a good one?

- Vince has had certain disappointments in his career. Do you have sympathy for the way he’s handled these disappointments, especially when it comes to their effect on the construction of the building?

- Pamela seems to have two sides to her personality—the one she shows to Dickie Sutcliff and others and the one she shows only to a few people, including Jack. What lies at the root of this dichotomy? What clues do we get from Pamela’s visit to her parents’ house?

- The action in The Building takes place in 1985. To what extent is the construction of the high-rise in Furnass a reaction to the decline of the steel industry in western Pennsylvania? How do the characters respond to these economic circumstances?

Reviews, Extra Scenes, etc.

Full Review – Kirkus Reviews

In Snodgrass’ (Kitchen Things, 2013, etc.) novel, a complex construction project teeters on the brink of failure, pitting workers against each other.

Furnass is an economically ailing mill town in southwestern Pennsylvania with some hope that a new high-rise building project will revitalize the area. However, Jack Crawford, the cantankerous job site superintendent, is ordered by his superiors at Drake Construction to delay the pouring of concrete columns. The company hasn’t received payment for months, partly the result of ballooning costs, and partly due to the collapse of the bank responsible for the project’s funding. The architect, Vince Nicholson, whose thoughts grandiosely toggle between the ideas of architects Mies and Le Corbusier, desperately tries to save a project that’s threatened by his own hubris.

Meanwhile, Jack conducts an extramarital affair with Pamela, a nurse who performs nude dance performances before her apartment window, to the delight of rapt construction workers nearby. Jack inexplicably introduces Pamela to workman Bill van Hayden, also a married man, and they begin a torrid affair of their own. Bill becomes increasingly infatuated with Pamela, and tells Jack of his intention to leave his wife for her; the resulting tension evolves into open animosity. Snodgrass displays virtuosic skill at relating the technical nuances of building construction. However, the chief strength of the book is how he profoundly captures his complex characters, who are each wounded in some ineradicable way. He even deeply develops supporting players, such as Gregg Przybysz, a newly minted building inspector trying to prove that he’s up to the task.

The prose is poetically ambitious and sometimes wildly unrestrained, which is well-suited to the pervasive sense of chaos and urgency: “…the bells of the Church of the Holy Innocents, the bells of the Angelus, ring out over the little town, ring out over the layers of rooftops to the hills on the other side of the river and back again.” The pace is unhurried but inexorable, a relentless march toward a shocking conclusion. This is a sinewy first installment in a planned trilogy—artistically unflinching and morally unsentimental.

An audacious, gripping, and wise novel.

– Kirkus Reviews

Full Review – Self-Publishing Review

The first book in Richard Snodgrass’ Furnass Towers Trilogy, The Building is an evocative work of literary fiction, in which the construction of an apartment tower acts as a pivot to unveil an eccentric cast of characters, allowing Snodgrass to deftly weave the stories of the people in this struggling mill town. Usually, with a cast this big, it is possible to lose focus and drain tension. However, The Building works in the opposite direction: every point of view reveals a little bit more and every switch has the satisfaction of putting the right puzzle piece into place – slowly making the picture whole. In between the story, there are long sections of italicized narrative that works to set the tone and adds a base to the canvas, which colors each character.

Snodgrass has also managed to make every point of view distinct, moving effortlessly between styles. Pamela especially sticks out as a favorite. Snodgrass does not fall victim to stereotypical portrayals of women – she has depth and carries herself through her narrative in such a way that makes the reader sad to say goodbye. “The Building” is the final character, which gives a framework for this curious group of characters’ conflicts with themselves, and with each other….

The prose itself is crisp and quite lean, which allows for an easy and page-turning read overall. The shining light throughout is the dialogue. Snappy and believable, it gives a real sense of place to the novel, and reveals the innate differences – and similarities – between these characters, who come from different walks of life. In the final part, there is clever use of unquoted speech that flows effortlessly with the scene, showing off Snodgrass’s chops as a prose stylist.

In all, The Building is a fine novel and sets up the rest of the trilogy well. This eclectic and well-drawn cast of characters will inspire readers to binge through the rest of the trilogy, as each character is innately recognizable, representing fears, insecurities, and hopes that drive all of us. Though on the surface it’s a novel about a single building in a small town, the novel has a big story to tell within an inventive literary framework, making The Building an ambitious and intricately woven work of literary fiction.

—Self-Publishing Review

Full Review – IndieReader

Verdict: The construction industry seldom is the topic of serious literature, but in THE BUILDING it rises to great heights, a distinctly American tragedy destined to endure on college reading lists.

Where there’s muck there’s brass. Or you might say, where there are bricks, concrete and rebar, there’s gold. As THE BUILDING demonstrates, there also is a sense of greatness and ownership that touches everyone involved in a major construction project. And there is always the possibility — both literal and figurative — of falling from great heights.

THE BUILDING takes place over a single day in the fictional city of Furnass, located in the Pittsburgh hill-and-river country of western Pennsylvania. The city’s steel mills are dead, so it’s a mystery why anyone would think it’s a good market for expensive residential towers. Julian Lyle, the building’s quixotic owner, is as blind to the financial excesses of his architect as he is to the disrepair of his offices.

But it is the novel’s anti-hero, Jack Crawford — the arthritic, mean-mouthed, hulking construction superintendent — who is willfully blind. Jack turns away from the emotional injury he causes. He fails to see impending danger despite compulsively watching out for the physical safety of all around him, including a young building inspector he derides for lack of experience and impels toward a terrible decision.

Richard Snodgrass is an art photographer who captures loss in his black and white “When There Was Steel” series appearing on his homepage. His writing is similarly elegiac due to keen sensory description as in the novel’s opening stream-of consciousness tour of Furnass. From dark to dawn, a breeze crawls the streets, strengthening and presaging trouble. This is the first in a number of lyrical, single sentence interludes creating a topography of the town and introducing different characters’ perspectives of the day’s events.

THE BUILDING is book one of what will be the Furnass Towers Trilogy. Like the Mississippi William Faulkner evoked in his Yoknapatawpha County novels, Furnass commemorates a slice of the Rust Belt as a singular place and time of sadness yet endurance. The construction industry seldom is the topic of serious literature, but in THE BUILDING it rises to great heights, a distinctly American tragedy destined to endure on college reading lists.

—IndieReader

5 Star—”IndieReader Approved”

Introduction to Extra Scenes, Etc.

Over the years since I started work on the Furnass Series, the novel The Building probably went through the greatest number of rewrites and revisions, a dozen or more. Working titles along the way included Sun Without Heat, Damian’s Folly (back when Julian Lyle’s name was Damian or maybe it was Sylvan—but that’s another story), Endo, and, of all things, Tower of Babble (that didn’t last long, thank heavens; we all make mistakes). The reason for all the rewrites was that every time I thought I had finished the book and started on the second book of the series, the characters in the second book would stand up and do something that required going back and revising that action of the first book. Then when I finally had the first two books in sync and moved on to the third, the characters again would do something that required going back to books one and two…well, you get the idea.

The following are some of the scenes that hit the cutting room floor along the way. Though the individual scenes might not have fit into the final scheme or structure of the book, they may provide you with additional insights into a character’s attributes or motives, or add to the overall flavor and texture of the mill town of Furnass.

Author’s Review of an early version of The Building

Once upon a time, close to twenty years ago, back when The Building went by the name Sun Without Heat, my agent at that time, in preparation for sending the manuscript out to publishers, asked me to write a review of the novel—a favorable review, of course, giving my insights as to novel’s qualities and strengths. Looking at the review now, it is very self-serving, as it was supposed to be, and at times presumptuous—I am endlessly grateful to the Powers that the book didn’t get picked up at that time by a publisher, it and the entire Furnass Series never would have developed as it has. Still, I’m including this review now because it shows a number of the author’s intentions and concerns that were present in the story from its inception.

Author’s Review of an early version of The Building

The time is the mid-1980’s. The glory years of the steel industry are over. The mills, around which life has centered in Furnass and other mill towns crowded along the rivers in western Pennsylvania, are shutting down. A way of life is gone. It is, as one of the more literate characters in Richard Snodgrass’ novel, Sun Without Heat, observes, “…the holding tank for the detritus of the Industrial Revolution. Burial ground for the old who can’t go anywhere else and the young who aren’t old enough to go anywhere else and the damaged turned loose from the asylums with nowhere else to go.”

And sticking up from the center of the little town, rising incongruously amid the boarded-up stores and rusting factory husks, is a high-rise building under construction. A local would-be developer named Sylvan [Julian] Lyle has a dream, a variation of the idea “If you build it they will come.” Through a series of shaky deals, Lyle has scraped together the funding for Furnass Towers, which he hopes will revitalize the town. Though his funding, and consequently Lyle’s misbegotten dream, begin to unravel through the course of the novel, the real story here centers on a few of the workmen who are building what another local businessman calls “Sylvan Lyle’s Tower of Babble.”

A number of contemporary writers weave their fictitious worlds out of the fabric of small town America—William Kennedy and Richard Russo come to mind. But rather than extreme characters placed in everyday situations, Snodgrass’ characters are everyday people facing extreme moments in their lives. (Incidentally, it was when Cormac McCarthy’s later novels made that same distinction that McCarthy’s work took on real power, the power from strength instead of shock.) Snodgrass is working within a definite tradition here—Joyce of Dubliners, or Faulkner, or Kesey of Sometimes a Great Notion—and the story evolves from the growing awareness of the characters’ desires and needs and choices. The important thing is that Snodgrass has taken that tradition and put his own stamp on it. And given it his own voice.

The central figure in the fugue-like structure of the book is Jack Crawford, the fiftyish, outspoken construction superintendent. At five-thirty in the morning on the day when the novel takes place, All Souls Day, Jack is told to cancel a concrete pour that he’s scheduled. Better at telling than at being told, Jack decides to make the pour on some columns anyway. There are rumors that his company might walk away from this project. Jack doesn’t think it’s safe to leave the columns without the concrete. But more to the point, he likes making his own decisions. A lifetime of hard work and hard play is catching up to him and he’s not used to a body that won’t always do what he wants it to. Pouring the columns when he’s told not to makes him feel like his old self again.

The rest of the novel proceeds from that decision, and we follow how it impacts both his life and those around him. Among the other characters is Pamela DiCello, a young nurse who lives across the alley from the project and with whom Jack has been romantically involved; Bill van Hayden, the ironworker foreman, whom Jack has introduced to Pamela when that relationship got too close for comfort, an introduction that Jack wishes now he had never made; Gregg Wiznicki, a young inexperienced inspector who is as much concerned with avoiding Jack’s bullying as he is with trying to determine whether the work going on is acceptable or not; and Vincent Koslick, the architect for the project, who is trying to balance the fact that he’s compromised his aesthetics as well as his ethics for a building he considers both a travesty and the highlight of his meager career.

Another character in the book is the town of Furnass itself. In a number of rondo passages, the action is momentarily frozen as we glimpse the broader life of the town as well as receive updates of what the various major characters are up to. The rondos also provide suspense and a sense of peril with foreshadows of the future, forewarnings of an accident later in the day that will change all of their lives.

The engine that drives this story is choice. There is Jack’s initial choice to pour the columns today. But more importantly, each character is faced with choices throughout the day, and each of the interweaving chapters has to do with a character’s choice—or failure to make one, which, of course, is another choice. Fueling this engine of choice is the characters’ sense of personal responsibility or lack of it. Koslick, the architect, is the most obvious example; he is facing the consequences of too often using another’s personal responsibility as a way to slough off his own. Early in the day, when Gregg, the young inspector, finds a problem with the welding on the reinforcing steel for the columns, he calls it to Koslick’s attention. But when Gregg asks the architect if the welding is acceptable the way it is, Koslick throws it right back on him:

Koslick turned to him. “Oh no, that’s not my job. That’s your job to tell me. You’re the inspector.”

What does he mean? What? “But I can’t say they’re okay if I haven’t seen them all. Can I?”

“No, you certainly can’t say that you’ve seen them all. Unless you want to lie, that is. But you can say in your report if the work you saw in progress is satisfactory or not. It becomes a matter of phrasing, I suppose. The choice of words…it’s up to you. You’re the inspector, it’s your job to look at things and report what you see. Whatever you say, we’ll have to go along with it.”

He’s turned on me, what did I do wrong? What am I supposed to do? They’re all looking at me….

Linked to this theme of personal responsibility is the characters’ level of self-awareness. As he watches Bill, the ironworker foreman, slip deeper into his troubled inner world, his friend Levon thinks,

…You got to keep your eyes on what’s going on around you, on what’s in front of your face, that’s where salvation is, man, the Buddha says the only sin is unawareness and let me tell you, bud, you’re about as unaware as they come right now…

As we see as the story evolves, unawareness can prove fatal.

Sun Without Heat is a complex novel that can be read on many levels. Each of the major characters is a reflection of facets of the others, point and counterpoint, and the various scenes and characters’ points-of-view weave in and out to present all sides of the story. Among other things, it is also a love story, the story of how Jack becomes aware that he’s tossed away the love of his life, and what it would take for him to pick it up again. Funny at times, tragic at others, the book is a rarity for readers: a good read that can both enliven and enlighten.

Prelude to The Building

[At one time, I wondered if the first book of the Furnass Towers Trilogy, The Building, needed something to tie it in more closely with the other two books. The result was the following Prelude to The Building, introducing the character of Reverend Bryce Orr, and more importantly, Julian Lyle, whose actions formed the ground and set into motion all the other actions of the three books. Once it was done, however, I decided it was far too explicit and heavy-handed in its setting of the moral stage, especially as the opening of the book—some of it appears in a later rondo. But after reading the book in its final form, you may find the scene of interest in regard to the intentions and concerns of the characters, as well as those of the author.]

Prelude

In which the wheels of our story begin to mesh and grind forward….

Inside the outer lobby of what was once the Alhambra Theater, Bryce Orr walked along the row of leather and brass studded doors, the leather cracked and peeling, the studs the color of old mustard, peering in each small dusty diamond-shaped window—he could see a few lights burning in the grand foyer, down the corridors beyond, he was sure someone was there—trying each door in turn and finding each door in turn locked. Until, as he might have predicted, the last one.

What’re you doing, Lord, he thought, playing with me, jerking me around? Of course it would be the last door. Why would I expect anything else in this best of all possible worlds? Wouldn’t have it any other way.

Through the door, the Reverend Orr, the Downright Reverend as Bryce thought of himself—an Avenging Angel, no, that’s too harsh, I’m more an Angel of Accountability, yep, that’s me, flexing my wings—chugged across the empty grand foyer, in his too-short raincoat and tweed walking hat pulled down over his ears, following the trail of occasional work lights, bare bulbs in broken sconces. The pretend-Moorish décor of the old theater was as he remembered from when he came here as a teenager, though it had seen better days—whole sections of the tile floor were missing, the plaster on the crenelated arches was crumbling, the decorative screens were vandalized. Beyond the lobby the interior had been ripped out in Julian’s attempt to convert the place into what he called the Alhambra Shopper’s Bazaar, several corridors of false storefronts painted to look like a Moorish marketplace in Marrakesh or Granada—what Julian supposed a marketplace looked like in Marrakesh or Granada—all of the windows empty, blacked out or covered over, the few shops that had been occupied abandoned now, the rest of the spaces never rented. Julian, Julian, Julian, Bryce thought, what were you thinking? Obviously you weren’t thinking. You never did have the sense the Good Lord gave a goose, did he Lord? Beyond the storefronts was an office door; he tried it but it was locked. In the dim light he could see where the word MANAGER had been scratched off the frosted glass and stenciled over with:

Julian A. Lyle, Esq.

Attorney-at-Law

Esquire? You got to be kidding me. Julian calls himself Esquire? Well, I guess that’s in keeping with the guy. As if Julian Augustus wasn’t bad enough. The Lyles always did have pretentions about themselves. The Jule of Jewels, as we called him when we were kids. On the other hand, they used to call me Dicey-Brycey. Nope, don’t want to go there. What can I tell you, Lord? Fascinating rhythm….

Bryce retraced his steps to the foyer, beginning to feel a little uneasy in the large empty building, starting to see things out of the corner of his eye—spooky ol’ me, heh heh, the Lord is my shepherd and all that—pretending to imagine things, trying to kid himself out of the uneasiness, Arabs wielding scimitars in the shadows, axe murders around the next bend in the corridor, Julian’s bloody mutilated body lying in a heap in one of the abandoned shops—you know I mean it, don’t you Lord? The Good Shepherd thing?

Back in the main lobby, feeling more comfortable within easy running of the street, he noticed there were lights up the grand staircase to the mezzanine, lights showing beyond the railing on the upper level. He stepped over the frayed red velvet and followed the trail of lights up the threadbare carpet on the steps, across the stained threadbare carpet in the mezzanine lobby, and up another narrower set of stairs and through another set of doors to the top of the balcony. The rows of seats were still in place in the balcony but the space in the main auditorium below was taken up by the ceiling framework of the various shops of the Shoppers Bazaar, the trusses and channels of the suspended ceilings, heating and ventilation ducts, the tops of lighting fixtures and junction boxes. Overhead only a few of the flame-shaped bulbs burned in the once grand chandeliers; on the stage a single bulb glowed on a light stand, in keeping with theater tradition, in front of the old movie screen that was wrinkled and cracked and hanging cattywampus. Julian sat in the center section a few rows from the railing, his arm draped over the back of the seat beside him as if around the shoulders of an imaginary companion, the collar of his old tweed sport coat pulled up against the chill in the building, the heavily padded shoulders, a style long-gone-by, making him appear as if he had shrunk inside the garment, a wool scarf wrapped around his neck. As Bryce made his way down the steep steps—he had to keep his feet canted to fit on the narrow treads, he remembered he had the same fear when he came here as a kid, that he was going to trip and roll down the aisle right off the end of the balcony—Julian turned to look over his shoulder at him, a non-committal expression on his face as if not in the least surprised to see him.

“I smell smoke,” Bryce said, reaching out for the back of the end seat on the row behind Julian to steady himself, then side-stepping along the row and plopping down several seats over so Julian could see him easily enough, slouching down so his knees touched the seatback in front of him, his hands in the pockets of his shorty raincoat, tucking the garment around himself as if in preparation for bad weather.

“I know,” Julian said. “We had a fire during the remodeling for the bazaar and the entire upper half of the theater filled with smoke. There’s not much ventilation up here as you can tell. We had a dickens of a time trying to air it out. An electrician was up on the catwalks a couple months ago and said there’s still a cloud of old smoke hanging around above the stage, you can actually see it.”

“I’ll bet I haven’t been up here since that time in high school when a bunch of us—I think there was you and me, Dickie Sutcliff, maybe the Binder brothers, I know there was somebody else, I don’t think it was Needle-Prick Brown the Insect Fucker, he was older, no reason for him to be along—it was for Senior English Class, we all came to see Marlon Brando in Julius Caesar. Et tu, Bruté. That’s all I can remember, that and Brando’s silly-looking knees in a short toga or something.”

“Didn’t you ever come up here with Rachel to make out?”

“Nah. Rachel wouldn’t let me touch her before we got married. I could barely get a kiss good-night out of her. She was the moral one in those days, the good Christian as it were. I was so frustrated with her I sometimes wonder if I didn’t go into the ministry just to get even with her. Heh heh.” Bryce looked up into the vast cavern of the old theater. Overhead in the darkness he could barely make out the mural high above on the ceiling. A band of angels fluttering through clouds toward heaven. The point of view showing the undersides of plump angelic thighs and cherubic bottoms. He turned his eyes forward again.

“How did you know where to find me?”

“I called your house. Marta said you were here, so I just kept poking around.”

“Sounds like the Reverend Bryce.”

“That be me.”

“Then there’s the question of why. But I can probably guess.”

“Yeah. I heard all about it.”

“Probably not all about it.”

“I heard enough that I thought I better come see you.”

“Who’d you hear about it from?”

“Harvey McMillan,” Bryce said. Adjusting the raincoat about himself, hands still in his pockets. Slouching a little further in the seat, making himself comfortable.

“Were you over at the bank?”

“At the church. He’s in my congregation, remember?”

Julian nodded once, an upturn of his head to show assent.

“He stopped by on the way home. I thought he wanted to talk about our loan for the new furnace. But then he told me about Sycamore Savings and Loan.”

“Is Harvey worried for the bank?”

“Doesn’t seem to be. He said it was only affecting Sycamore. That people had been making a run on it all day, taking their money out.”

“I wouldn’t call it a run at this point,” Julian said, stretching both arms along the tops of the adjacent seats, then resettling himself, his hands in his lap. “More like a brisk trot.”

“Any truth to the rumor that Sycamore won’t open on Monday?”

“I don’t know. I tried to talk to John Bagley—”

“He’s still president?” Bryce interrupted. “Ol’ John?”

Julian looked at him and continued. “—today but he wasn’t taking any calls. He’s certainly not helping matters, not talking to people. The ‘run,’ as it were, will become a self-fulfilling prophesy.”

“But that’s not your real problem,” Bryce said, yawning without really having to.

Julian looked at him again, as if to see what he was up to. “It’s certainly problem enough. If Sycamore closes its doors, they won’t be making any more payments for the construction loan. And without payments on the construction loan, I can’t pay the contractors and sub-contractors on the Furnass Towers.”

“Harvey says you haven’t been paying them anyway.” Bryce raised his eyebrows at him, made a tight-lipped smile as if to say Gotcha.

“So you have heard a great deal.”

“Harvey was certainly concerned. About the far-reaching consequences.”

Julian sighed. He looked ahead at the blank screen over the ceilings of the abandoned and empty shops. “No, the contractor hasn’t been paid for a while, because Sycamore hasn’t been paying us, it seems they’re over-extended and cash is low. And when news of that leaked out, some people began withdrawing their funds, which got more people scared and started withdrawing their funds too. And when Sycamore’s creditors heard all this was going on, they started to call in their loans, sinking Sycamore even further. To say nothing of the fact that the cost of construction is way more than was ever anticipated, or estimated. We were going to have to ask for an additional loan anyway, so that’s now obviously out of the question.”

“Any chance of a loan from First City?”

“They didn’t want the financing for the project at the beginning, they certainly wouldn’t want it now. That’s why we had to go with the Savings and Loan in the first place. First City only handles the accounts for the Development Corporation.”

“Whew!” Bryce said. “What a mess.”

“ ‘Whew!’ would be an understatement.”

Bryce sat there shaking his head. Then he laughed a little, aware that it wasn’t funny, but still struck by the irony, the absurdity of the world’s affairs. “So. What are you going to do? What can you do? I guess that’s the end of the Furnass Towers.”

“I wouldn’t say that,” Julian said.

“Well, you owe money for past work, and there’s no more money for future work. Seems to me you’re out of work.”

“I’m not going to pull the plug on it just yet, if that’s what you’re thinking. Something could still….”

“But can’t let the contractor keep going, can you?

Julian smiled a little, looked at Bryce, and then looked away again. “You really don’t know how the world operates, do you, Reverend?”

“I know what the moral thing to do is.”

Julian shook his head, regretful, though Bryce wasn’t sure about what.

“You’ve got a responsibility to other people, that’s what morality is all about,” Bryce went on, sitting up, warming to one of his favorite topics. “You can’t let the work go any further, if the contractor isn’t going to get paid for it. The moral thing to do is to tell them so they—”

“Why did you come here this evening, Bryce?”

Bryce looked away, into the shadows of the old theater. “You know, I’ve been thinking a lot about angels lately. I think I’ll do a sermon on them. What they are, what they do. We tend to think of them as these great glowing bigger-than-life figures all in white, wings sprouting out of their shoulders, but maybe they aren’t like that at all, at least most of them. Maybe they’re just normal-looking everyday guys but with a kind of charisma about them, you know? Something that draws you toward them so you find yourself listening to their message—”

Julian stood up, raised his arms above his head, knuckles locked, stretching his spindly runner’s body—of which Julian was always proud though in these later years reminded Bryce increasingly of Ichabod Crane—stepped out in the aisle, took one more look at the scene below, then turned to Bryce.

“Well, old friend, I can tell you you’re no angel, if that’s what you’re trying to get at. I have no doubt that in your mind you came here with all good intentions, but what it amounts to is your telling me all the things you think I’m doing wrong. It’s no different than when we were growing up on Orchard Hill, though then you didn’t cached it in some grand religious, metaphysical context. It was just Bryce being Bryce. So thanks, but no thanks. I’m glad you came here tonight, because it really helped me see what I’m going to do. No, I’m not going to say anything to the contractor, I’m going to wait to see how things play out before I make any more moves. And if that makes me one of the fallen in your book of righteousness, so be it. Free will’s a bitch.”

Julian raised his eyebrows at him as if to say So there and headed on up the steps. Bryce listened to the Whoosh of the doors at the top closing behind him, the click of Julian’s boot heels across the tile floor growing faint. He squirmed a bit in his seat, worked his shoulder blades against the curved wooden back. This theater never was that comfortable, even when we were kids. Julian’s right, I’m no angel and I wouldn’t want to be. Those wings would be hell trying to fit into a little seat like this. Always getting in your way. Knocking over little old ladies, scaring the cat. Heh heh. Crazy, man, crazy. Far out. He looked up once more into the darkness at the plump under-thighs and bottoms of the cherubs ascending overhead in the mural, then stood up, shaky at first, steadied himself on the center railing, and made his way up the carpeted steps and out the door, back the way he’d come. Thinking, Well, that didn’t go well, did it Lord? Is he really going to let the work continue on his Tower just because I told him he shouldn’t? Yeah, probably so. Crazy stuff. I get it that ol’ Julian doesn’t believe in moral absolutes, religious certitudes. Funny position to take for a confirmed Covenanter but I never did get all that praying to the God of Love and then go slaughter the English cavalry stuck in a bog. Anyway, the Lyles always were full of hubris, along with bullshit. But if he thinks the rules of conduct don’t apply to him, how does he make it through the everyday? How do you live in a world if you don’t believe in anything? Ol’ Julian the Jewel. Fascinating rhythm….

…as downstairs in the old theater, in the defunct Shopper’s Bazaar, Julian stands in the darkness of an empty storefront that for a brief time—a very brief time—housed Annatello’s Studio of Dance, standing off to the side but with a view of the front windows, waiting until he sees Bryce wander down the corridor toward the main lobby, thinking Dicey-Brycey, I suppose you mean well, you’re too flakey to have a malicious bone in your body, minister as hipster, a bebop pastor as he likes to bill himself, but it’s the last thing I need right now, one more person telling me how wrong I’ve been, what a fool I am, as if I didn’t know already, as if I needed to be reminded of all my failings, of all my failures, waiting in the darkness to give Bryce time to reach the front of the building then goes to the door and cracks it slightly, listening for the Swish! of the outer lobby door closing, then makes his way, still being cautious in case Bryce is pulling a stunt, to the main lobby, looks out the small diamond-shaped windows in the padded doors to see if the coast is clear, then goes through to the outer lobby and locks the doors to the sidewalk before returning and locking the inner lobby door, returns through the theater past the bazaar to his office, unlocks the door and goes through his secretary’s office in the dark and into his own office, thinking he’ll take one more look at the books, maybe he missed something, maybe he read something wrong, maybe things aren’t as bad as he thinks they are, turns on the library-style lamp with its green glass shade and sits at his desk and opens up the ledger books one more time, but within minutes his eyes begin to glaze over—more than that, begin to tear up, but he won’t stand for that, won’t allow himself that indulgence, he shakes his head violently to clear his thoughts, his mind—closes the ledger and turns off his desk lamp again and makes his way back through the dark offices to the corridor again, locks the door behind him and makes his way down the corridor to the master light panel, throwing the switch that plunges the building into darkness and then feels his way to the back door, hits the panic bar and bursts out into the lighter darkness of the night, the chill air against his face refreshing as a moist washcloth on his skin, takes a deep breath of the night air, grateful despite everything that is happening to him to be alive, to have the chance to still make things right, hurries down the fire escape, his footfalls ringing dully on the metal treads, to his car parked in the lone spot behind the building, backs out into the alley and heads down the side street and turns onto the main drag, heading up through the town that’s all but deserted now at ten-thirty at night, only an occasional car on the street (where the street used to be jammed at this hour with the cars of mill workers heading for the graveyard shift), only an occasional figure on the sidewalks (where the sidewalks at this hour would be busy with guys heading for the bars after work for a shot-and-a-beer before going home), past the dark skeleton of a building under construction, what was to be the Furnass Towers Office and Apartment Building, the ten-story concrete framework behind the construction fence dominating the little town, the narrow main street and the two- and three-story buildings around it, Julian’s attempt to revitalize the town now that the mills have closed, this town that he calls home, that his family more or less founded close to two hundred years earlier and that he feels is his responsibility or duty or at least legacy—maybe fate; maybe doom—to try to do everything he can to save from dying like the other mill towns in the river valleys around Pittsburgh, but he can’t think of any of that now either, though he knows all too well that he thinks of little else these days, passes the offices of Sutcliff Realty, Dickie Sutcliff’s office, another kid he grew up with in town who now leaves something to be desired in the friend category, another person interested in trying to revitalize the town but on his own terms, those terms apparently based on doing Julian out of every source of available financing, a guy to whom all through his life, whether in games of three-feet-across-the-street or backyard baseball or pick-up basketball games in the alley behind Sonny Rourke’s, that Julian seems fated—maybe doomed—to be second-best (if he’s lucky: it seems more like third- or fourth-best, at best), wonders aloud, God damn it, what the hell do I have to do? What the hell did I do wrong? with a touch of self-pity perhaps but mainly with a genuine bewilderment not only at his lack of success in all his ventures but what appears to be abject failure at everything he attempts, a genuine curiosity why it is in this world that some people seem destined to rise and others to fall, and how ethics and morality function in such a world, how the Bagleys and the Sutcliffs who don’t give a hoot about other people can flourish while others who genuinely try to do the right thing fall by the wayside, a genuine puzzle, Julian thinking again of what Bryce said this evening, You’ve got a responsibility to other people, that’s what morality is all about, and wishes he was so certain as to what morality is all about, wondering where in all this the responsibility to himself fits in, turns at 24th Street and heads up the long winding hill out of the valley, up Downie Hill Road, heading to Furnass Heights and home where he knows already he’ll spend another sleepless night, not afraid to close his eyes but constitutionally unable to let go of consciousness and allow sleep to overtake him, the ability to sleep beyond him because of the dreams he knows on some level of his consciousness or subconsciousness are there waiting for him, the dreams of endless hallways and dark corridors and something in the darkness around the next corner that is waiting to stir, turning slowly on its giant web, feelers waving testing the air, the multi-faceted thousand fractured eyes just beginning to focus on him…and the long night continues….

From Revision 2011

but the mill is closed now, and the town is still here…life goes on in the town, in many different forms, as on this morning of the Day of All Souls, in a sycamore tree along one of the steep, brick-paved streets leading up the hill from the river, a blue jay lands among the few remaining leaves and calls raucously to see if there are any other blue jays in the neighborhood…a family of finches and a few wayward sparrows peck their way through the tray of a back yard bird feeder looking for the millet among the sunflower seeds before the starlings arrive and drive them off…two cardinals run up opposing sides of a garage roof, each one looking for the other, almost collide at the top and go scurrying off in opposite directions with a flurry of wings…a half dozen crows dance in the air above a squashed hamburger in the empty parking lot of the Giant Eagle while one of their number keeps a solitary watch from the steeple of Holy Innocents…and if anyone in town sees or hears these goings-on, they think, at best, “Dumb birds,” or, more likely, “Shoo! Go away!” the sounds of the mill carrying over the town until they became those of the town…

From Revision 2015

…and the afternoon wears on in the valley, and the river continues to wear away its channel between the hills, as it has since the last finger of a glacier scraped the valley from the landscape before retreating again, here at the farthest reaches of the Ice Age…the river flows on as darkness gradually settles over the town, the days growing shorter in early autumn, evening coming too soon for most people, anticipating the dark days of winter …the sky turns from dirty gray to dirty black, a starless night because of the blanket of clouds over the valley’s hills, though above the ridgeline across the river from the town there is a touch of red, a slight glow, from the lights of Pittsburgh a dozen miles or so to the south, and to the west a flickering orange from a mill still in operation at Alum Rock or somewhere further down the Ohio…in their homes people are settling down now to eat and watch the evening news, watching for pictures of the accident to find out more of what happened and if anyone was hurt and perhaps catch a glimpse of some place or someone they know, “Oh look! Look! There’s what’s-his-name,”… the story of what happened in town today being told and retold, lived and relived, in the minds of those whose lives are one with the life of the town, the story changing as it goes, wearing the course of its channel deeper and wider depending upon who is doing the telling and living, the story-now and the story-then and the story-to-be like the lights of the town reflecting on the river, skeins of silver that spread and unravel and drift away and form again into new shapes on the black surface of the water as the river continues on…the streets of the town empty now, only an occasional car passing along the main street where earlier this afternoon the street was choked with emergency vehicles…the last man standing up and down the sidewalks of the town being Dickie Sutcliff as he leaves his building, the offices of Sutcliff Realty, makes sure the door is locked behind him, then stands on the empty sidewalk, after staying late after the rest of his office staff left to review his contract establishing his limited partnership on the Furnass Tower and Apartment Building, confirming that as the limited partner to the project he is under no liability in regards to any of the recent events, satisfied that he has in fact covered himself sufficiently and is free and clear no matter what happens to the building now, takes a deep breath of the evening air and looks at the partially finished building a few blocks away, the stack of dark slabs and the remaining columns rising above the older buildings along the narrow main street—he wasn’t in the office at the time of the accident, he was out at Seneca Towne Centre, his townhouse and shopping plaza development in the hills beyond Furnass, playing racquetball with Pamela DiCello, but his employees filled him in about what happened when he got back to town—and thinks this will be the coup de grace for the project, finishing off what the impending failure of Sycamore Savings and Loan started, thinks It’s really too bad that anyone got injured on the site today but it looks like I have another property, if I want it, shakes his head and thinks, Poor Damian Lyle, he can’t win for losing, starts toward his car parked around the corner on 15th Street when he sees his reflection in the storefront of his building, shrugs to his best friend in the glass and says, “And I can’t seem to lose for winning”….

How Do You Say Przybysz?

The pronunciation of Gregg’s—“with two g’s”—Polish last name is

Shēb-ish

Naturally enough, many families in Western Pennsylvania choose to make it easy on their neighbors and on themselves by changing the spelling to the phonetic Shebish.

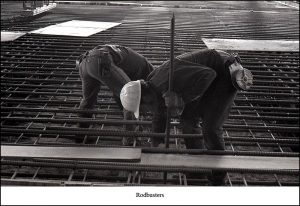

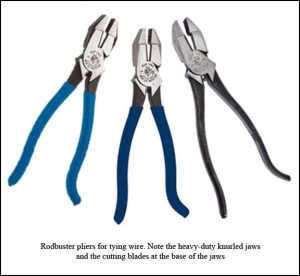

What is a Rodbuster?

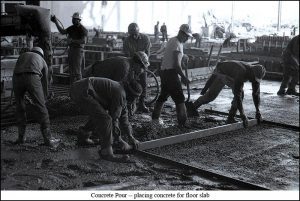

All rodbusters are ironworkers, but not all ironworkers are rodbusters. The term rodbuster refers to workers responsible for placing reinforcing steel bars—commonly referred to as rebar—in the forms where concrete will be placed to create reinforced concrete. But before going forward, we should probably explain what is reinforced concrete.

Concrete on its own is strong in compression, but not in tension—it’s good at withstanding forces pressing against it but not in trying to stretch it. Conversely, steel is good in tension—it can stretch—but not good at withstanding forces pressing against it—it tends to buckle. So, by combining the two building materials, you get the best qualities of each.

Of course, for the final material to reach its design strength, each material must meet certain standards. The concrete must reach its designed compression strength, which depends essentially upon the ratio of water added to the cement. Likewise, the rebar must meet its required tensile strength—and it must be placed, and kept in place, at exact spacings and locations within the forms.

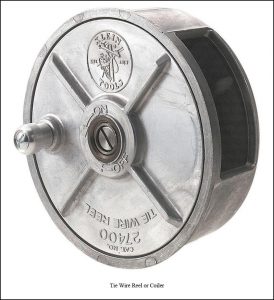

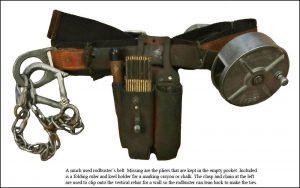

That’s the responsibility of the rodbusters. In addition to the manual labor of humping the heavy steel bars into place according the drawings—the finished layout looking like a multi-dimensional, multi-squared game of tic-tac-toe—the rodbuster uses steel wire and pliers to tie the bars into place.

First a length of wire is pulled from the coiler, then the end is wrapped around an intersection of the bars; the nose of the pliers is used to tie a knot in the wire, and the knife-like jaws at the base are used to snip off the wire from the coiler. Though it all happens within seconds the ties are critical to keep the bars in place while the concrete is placed around them. An inch or so out of location, and the rebar might as well not be there at all.

The image gallery above shows the tools of a rodbuster and below are links to the standards for placing reinforcing bars and inspecting the work from the Concrete Reinforcing Steel Institute (CRSI).