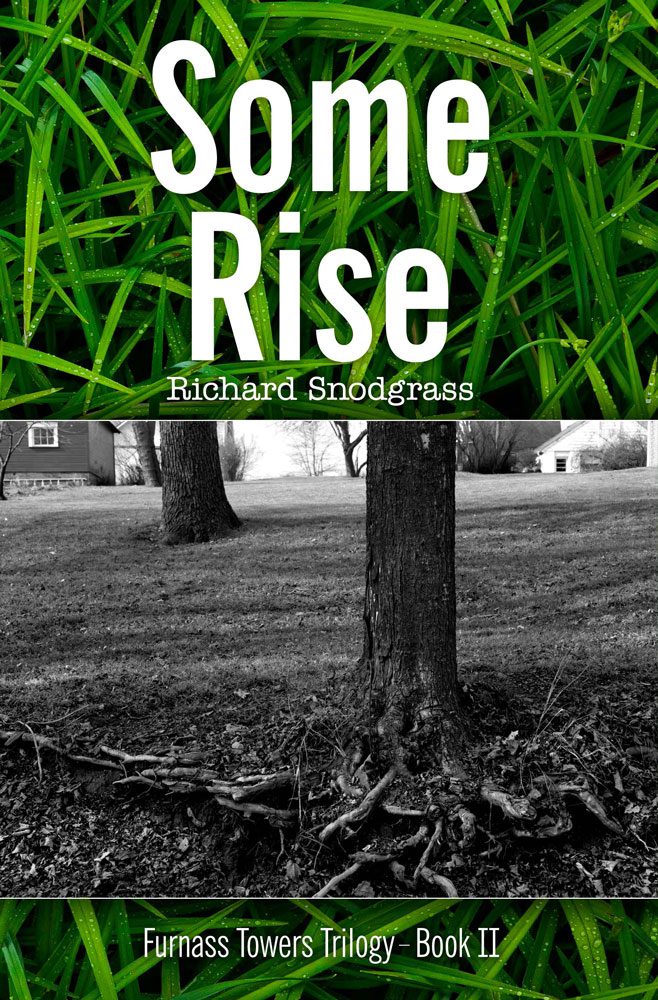

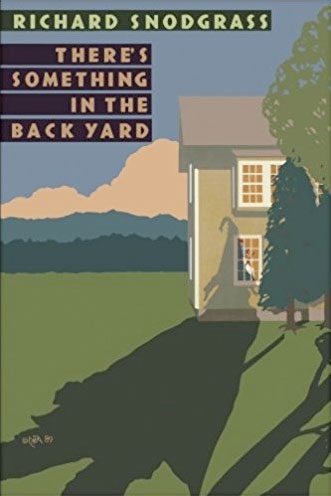

There's Something in the Back Yard

By Richard Snodgrass

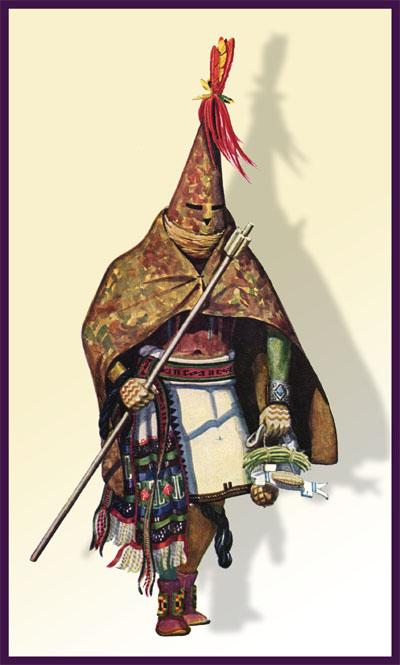

George Binns, a professor of English at a university in Flagstaff, Arizona, is called away from the typewriter one morning by his wife, Mary Olive: “There’s something in the back yard.” What George sees is a Hopi kachina, the Aholi, dressed in a long, colorful mask and a tall blue conical head. Challenged by his wife to “do something about it,” George runs outside and confronts the kachina—and is jolted forever from his comfortable routine. Over the course of four days, as the kachina remains a shadowy figure in the yard, George and the Aholi form a strange kind of relationship, one that precipitates several awakenings in George’s life. Most important is the awakening in George’s marriage, as he picks up the gauntlet dropped by Mary Olive and accepts her challenge to act.

Other characters are drawn by Snodgrass with equal sympathy: the Binnses’ neighbors, scholarly Don Pike and his wife, Sally, whose relationship is also affected by the appearance of the kachina and whose marriage comes to a head along with the Binnses’; the mysterious Hopi elder David Lomanongye, keeper of secrets; and, last but not least, the Aholi himself, whose partly comic, partly terrifying presence serves as a catalyst of these events. This tantalizing thread of the Unknown is woven throughout the tale told with otherwise old-fashioned realism; the result is a book of great lyrical depth and stylistic authority, with stabs of hilarious black humor.

“Observe this mysterious book and be changed.”

— Jack Stephens, The Washington Post Book World

“A striking debut.”

— Kirkus Reviews

“A haunting, seductive, original story.”

— Publishers Weekly

“This well-tempered, comically rueful novel is a skillful blend of Hopi legend and middle-class marital lore.”

— The Christian Science Monitor

CLICK HERE FOR FULL REVIEW

“Original and amusing.”

— Chicago Tribune

CLICK HERE FOR FULL REVIEW

“A playful, reader-friendly novel that satisfies with just the right mix of realism and metaphysical speculation.”

— Booklist

“The novel sticks in your mind.”

— Los Angeles Times

CLICK HERE FOR FULL REVIEW

“A measure of [Snodgrass’s] considerable skill [is] that he makes this stubborn, darkly comic novel convincing.”

— The Philadelphia Inquirer

Video

Promo

Video

TRAVELS WITH THE CORN DANCER

After THERE’S SOMETHING IN THE BACK YARD was reissued through Amazon.com’s CreateSpace, Richard Snodgrass and his friend, Jack Ritchie, take a road trip to the Southwest to promote the book to local bookstores— and along the way return a kachina doll to the Hopi Indian Reservation in Arizona.

ORIGINAL NOTE FOR THE NOVEL

This is my original note for a novel that eventually become There’s Something in the Back Yard. It was written, more or less stream of conscious in one sitting, during the summer of 1977 while I was on a residence fellowship at the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation in Taos, New Mexico.

The idea for the novel came after attending a number of ceremonial dances at nearby Indian pueblos that left a deep impression on me. I began to read everything I could find on Pueblo Indian culture, which led me to the Hopi whom the other pueblos considered the Keepers of the Universe. At the same time, I encountered a short story by Evan Connell entitled, “The Condor and the Guests.” It is the story of a suburban couple who have a condor chained to a perch in their back yard during a cocktail party. Truth be told, when I read the story I didn’t like it all that much, but it obviously left an impression as well.

Reader’s Guide to There’s Something in the Back Yard

Summary

There’s Something in the Back Yard tells the story of George Binns, an English professor at an unnamed university in Flagstaff, Arizona, who wakes up one morning to find a Hopi kachina, the Aholi, standing in his back yard. Is it real? Is it human? Is it a spirit? Unfamiliar with Native American traditions, and curious about this silent yet sentient being that seems more benevolent than threatening, George begins to research the matter and seeks answers among the local Hopi population. His wife, the sharp-witted Mary Olive, shares neither his curiosity nor his serious, earnest way of approaching the apparently otherworldly visitor. George’s scholarly neighbor Don doesn’t want anything to do with the kachina and insists that his own wife, Sally, a naive but passionate enthusiast of all things Native American, be kept in the dark about the kachina’s presence. Over the course of four days, as the Aholi remains a shadowy figure in the yard, emotional undercurrents in the couples’ relationships come into sharp focus, and George and Don both realize they have to make important choices. This beautifully written novel, woven throughout with the tantalizing thread of the unknown, offers both wisdom and humor while gently illuminating, as one character puts it, “the terror and glory of ever having lived.”

Questions and Topics for Discussion

- Who—or what—is the kachina that appears in George’s back yard? Does the author answer this question at the end of the book?

- George, Mary Olive, Don, and Sally perceive the Hopi, and Native Americans in general, through four different lenses. How do their perceptions differ? Which viewpoint would you say is the most accurate?

- There’s Something in the Back Yard follows in the literary tradition of “The Bear,” The Mountain Lion, and other stories insofar as it involves humans confronting a creature symbolic of an aspect of the natural world. What does the kachina symbolize in There’s Something in the Back Yard?

- What does Don’s unpublished manuscript, Retold Tales of the Hopi, tell us about Hopi legends? How should one show respect for cultural and ethnic traditions other than our own?

- Despite his inability to take action in certain situations, what compels George to take action when he sees the kachina? Why did the author choose to put George at the center of the story—as opposed to Mary Olive, Don, or Sally?

- How does the author use humor in the story? Does the humor lighten dramatic moments or heighten them?

- Snodgrass is one of a number of authors who have written about Native American themes, including Louise Erdrich, Leslie Marmon Silko, and N. Scott Momaday. How does Snodgrass’s approach to these themes differ from those of these other writers?

- Early in the book, Don recalls a passage from the writings of Carlos Castaneda: “When it’s time to die, Death comes and takes you to a place that has been special to you in your lifetime, a place that has been a place of power for you.” What does this passage mean to you, and where else do you see Castaneda’s influence in There’s Something in the Back Yard?

- Mary Olive and Don seem to share the same outlook on life, whereas Sally and George share a different outlook. Yet each is paired in marriage with his or her opposite. What holds the couples together?

- At the end of There’s Something in the Back Yard, George says, “A man’s work has value in itself, whatever the work is.” This provokes a heated discussion with Don. Do you agree with George’s statement and its implications for the artifacts we leave behind?

RETOLD TALES OF THE HOPI

Retold Tales of the Hopi is a book within the book of There’s Something in the Back Yard. In the story of Back Yard, Don Pike, a professor of English, gives the manuscript for the Retold Tales to his friend and colleague, George Binns in the following exchange:

“If you want to read something about Indians, maybe this’ll interest you. It’s something I wrote a couple of years ago. I guess it was ten years now.”

“Don, I’m flattered-”

“You don’t have to be. There’s a couple of things in there about your friend Aholi, so maybe it’ll give you some idea about how a Hopi thinks-no, I take that back, maybe it’ll give you some idea about how a White-Eye thinks a Hopi thinks.”

The distinction-between what a Hopi thinks and what a non-Hopi thinks-is crucial to the story of the book. Because misunderstanding is at the heart of everything that happens in Back Yard.

Retold Tales of the Hopi were written during the month and a half I spent camped out under a juniper bush on the Hopi Reservation in the summer of 1978. At the time I had already written a first draft of Back Yard while on a grant in Taos, New Mexico, and knew that I wanted to include the Retold Tales, both as background for the Hopi in general-to demonstrate in an amusing, readable way how different their view of the world is from the predominant American culture-and as a reflection the character of Don Pike who is credited in Back Yard with writing them.

During the 1960s and 1970s, A number of American fiction writers were working under general theory of “include-everything-you-can-think-of: the-bigger-the-book-the-better.” In particular, I was influenced by Ken Kesey of Sometimes a Great Notion, and John Gardner from such books as The Sunlight Dialogues and October Light. After a year of reading everything I could about Hopi myths- from my visits to various Southwest libraries, I probably had the largest Xeroxed library of Hopi tales in existence-I traveled to Hopi to watch the various Home Dances on the weekends. Between dances, I sat at a picnic table near the Visitor’s Center and worked on the Retold Tales.

The Tales may be considered irreverent, though I hope they’re not perceived as disrespectful. They were meant to be disarming and accessible. In writing them, I had the model of the Miracle Plays of the Christian Middle Ages, where the most serious matters of faith were treated off-handedly and sometimes with slapstick humor-a telling of the Crucifixion, for instance, from the point of view of the soldiers assigned to do the act whose hammer breaks and they run out of nails. Among the major misunderstandings portrayed in the book is the idea that there may be spiritual realities right under our noses that we’re failing to see. The Hopi in the book represent a people whose awareness of the spiritual is so strong they can even withstand the silliness and misperceptions of the characters in the book.

In Back Yard, only a few of the Retold Tales appear. Included here is the entire manuscript.

MORE TALES OF THE HOPI

H. R. Voth was a missionary and ethnologist didn’t do the American Indian culture any favors, particularly the Hopi. However, we do owe him for the survival—in some degree of truth or other; it’s entirely possible that his Indian informants gave him incorrect information—of a number of Hopi myths. As a missionary, Voth believed that the American Indians would not progress without rejecting native culture. While he saw dissolving the “heathenish culture” as his task, he studied the language, dances, and customs with zeal, publishing accounts in educational journals. In the 1890s he and his wife founded the first Mennonite mission for the Hopi at Oraibi, in Arizona. He earned a controversial reputation for forcing his way into Hopi sacred rituals and preaching loudly in the Hopi language. Again, while he focused on ending native customs, Voth carefully recorded Hopi rituals and daily life, collecting an impressive array of artifacts later loaned to the Field Columbian Museum in Chicago. In 1912 lightning struck the church he had finished in 1902, and more than a few Hopi thought that Voth’s work got what was coming to it.

To visit website:

http://www.archive.org/details/traditionsofhopi08voth

THE AHOLI AND WALPI KATCINAS

Alíksai! In Wálpi and Sitcómovi they were living, but not at the places where the villages now are, but where they used to be. In Wálpi lived an old man, the Ahö’li Katcina. He had with him a little maiden who was his sister, the Katcín-mana.

As he was very old and feeble this maiden would always lead him. In the other village, Sitcómovi, lived a youth with his old grandmother, and as she also was very feeble he took care of her and used to lead her. One time the Ahö’li and the little maiden went to their field ‘south of Wálpi where they wanted to plant. They carried with them little pouches containing seeds. In their field was a báho shrine, and when they came to their field the Katcina first deposited some prayer-offerings in the shrine, first some corn-meal and then also some nakwákwosis which he drew forth from his corn-meal bag.

This bag he had tied around his neck. In this shrine lived Mû’yingwa and his sister Nayâ’ngap Wuhti.

“Have you come?” Mû’yingwa said. “Yes, we have come,” they replied. “Thanks,” Nayâ’ngap Wuhti said, “thanks, our father, that you have come. You have remembered us. No one has thought about us for a long time and brought some offering here, but you have thought about us.” And she began to cry. Hereupon Ahö’li gave to each one a stick upon which some nakwákwosis were strung, and also some cornmeal.

Hereupon Nayâ’ngap Wuhti was crying still more. “Yes, we have come here,” the Katcina said, “we are pitying our people because they have not had any crops for a long time, and now we thought about you here and have brought these prayer-offerings here. And now you pity them and let it rain now, and when it rains then a crop will grow again and they will have something to eat, and they will then be strengthened and revived, because they are only living a very little now.

Hereupon he took out his little bundles of seed and gave to the goddess a small quantity of yellow, blue, red, and white corn as an offering. These he placed before her on the ground. The two deities then arose. Mû’yingwa had in his left hand a móngkoho, móngwikuru, and a perfect corn-ear (chóchmingwuu). These he pointed upwards towards the sky.

The female deity held in her hand a squash, which was filled with all kinds of seeds. As Mû’yingwa pointed up the objects towards the sky; she raised the squash with both hands and then forcibly threw it on the ground on the seeds which the Ahö’li had placed there. “There,” she said, “in this way I have now planted for all of your people these seeds and they will now have crops.” Thereupon Mû’yingwa handed the objects which he held in his hand to the Katcina, saying, “You take these with you and with them you produce rain and crops for your children, the people in Wálpi.”

So the Ahö’li and the Katcín-maha returned, first going to their booth, or shelter (kísi), that was near by in the field. Here they partook of the food, which they had brought with them. “Thanks,” the Ahö’li said, “thanks that our father was willing. We shall not now go back to the village in vain.” “Yes, thanks,” the mána also said.

Hereupon they returned to the village. It was now late in the afternoon. As they passed the top of the mesa upon which Wálpi is now situated, they heard somebody singing on top of the bluff, but they went on, and arriving at their kiva they sat down north of the fireplace and smoked over the objects which they had brought with them. “Thanks that we have returned,” the Ahö’li said, ”that we have not been too late for our people. We shall now possess our people.” And as they were smoking and thus talking somebody came and entered the house. It was the youth who lived with his old grandmother in Sitcómovi.

He came in. “Thanks that you have come,” he said, “thanks that you have come and provided something for our people here,” hereupon he shook hands with them. “Sit down,” Ahö’li said, “and smoke, too.”

So the youth filled the pipe with tobacco that he had brought with him and also smoked over the objects. He took special pains to blow the smoke in ringlets upon the objects. After he had done that four times, also praying to the objects, they became moist so that the water was beginning to flow from them, indicating that their efforts had been successful and that these objects would produce rain, which was symbolized by this moisture.

Hereupon the youth prepared to return to his home, but Ahö’li restrained him and said: “Now, tomorrow when the sun rises we shall make a prayer-offering and you must do the same, because when we came we heard somebody sing away up there somewhere.” So early the next morning they dressed up in their costumes, the Katcina being dressed in a tû’ihi, a kilt, and his mask; his body also being painted nicely.

In his right band he carried a stick, natö’ngpi, to the middle of which were tied beads and a bundle of báhos. In his left hand he carried the objects which he had obtained the previous day. The mána was dressed as the Katcín-manas are yet dressed today. She carried in her left arm a tray (póta), containing different kinds of seeds. They proceeded to a báho shrine west of the present village of Wálpi, halfway down the mesa. Here they sprinkled a little meal to the sun and on the shrine, this little rite being called kúivato. As they were performing this rite they again heard the same voice singing on top of the mesa, which they had heard before.

There were then no villages on top of the mesa, but the shrine of Taláwhtoika was there already, and at this shrine someone was singing. When looking up they say that it was the Big-Horn (Wopákal) Katcina. Hereupon they returned to their house, but immediately started up on the mesa to look for and meet the one that they had heard singing. So they went up and reached the top of the mesa somewhat west of the bahóki. Here they noticed some one dressed in a white mask with very small openings for the mouth and eyes. His body was also white and he wore a thin bandoleer with blue yarn over his shoulder. He was standing by the side of the shrine shaking a rattle of bones slowly up and down.

After having shaken the rattle four times he started off. “Wait,” the Ahö’li Katcina said, “wait, we have heard some singing up here and want to see who it is.” “Yes,” the other Katcina, which was the Â’ototo, replied, “yes, I am not singing, but we are two of us here, and the other one was singing.” By this time the Big-Horn Katcina came from the west end of the mesa holding in his left hand a bow, and having a quiver strung over his right shoulder. He had a green mask with a big horn on the right side and an ear on the left.

He wore a nice kilt, nice ankle bands, and his body was painted up nicely. When he arrived at the shrine he asked the Â’ototo: “Why do you tarry here?” “Yes,” the Â’ototo replied, “these are detaining me.” “Why?” the Big-Horn Katcina asked. “We heard somebody singing here,” the Ahö’li replied, “and we came up here to see who it was, and so it is you. Now, what do you think,” he continued, “let us go down all together and then we shall possess the people,” and he told the Katcinas about what they had obtained and were going to do. So the two Katcinas were willing and they prepared to go down.

The Â’ototo took the lead and was followed by the Ahö’li Katcina, and the mána, the Big-Horn Katcina coming last. This way they went down a part of the way at a place west of the present village of Háno. Here they made a báho shrine (bahóki), erecting some stones as a mark between the villages of Háno and Sitcómovi. This shrine is still there. They then went farther down to the present gap north of Háno to the large shrine with the twisted stone which is still there, Here they met somebody coming out of that shrine and then going up and down there. It was somebody dangerous (núkpana), who had large protruding eyes and a big mouth in his mask, and many rattles around his body and along the front part of his legs. His arms were painted white, his body red. Around his shoulders he had a small blanket of rabbit skin. On his feet he had old, torn, black moccasins. In his right hand he had a large knife, in his left hand a crook, to which a number of mósililis were attached. It was the Cóoyoko, who used to kill and devour children there. When the Katcinas saw him they said to him: “Do not trouble us, we are going to possess these people here. We are going home now. You can destroy the bad ones, since you are bad anyway, but do not trouble us.

Hereupon they descended and went to their home. When they arrived at the house of the Ahö’li, which was a very beautiful house, the Ahö’li said: “Now, here we are, and you stay with us. It is not good down here it does not rain, but up there where you are it is better. When it will rain here you can go back, but we want to help the people first. So tomorrow morning we shall go to the fields and plant for the people.”

During the night they did not sleep but they were singing all night, on their masks, which they had standing in a row in the north side of the room. When the yellow dawn was appearing before sunrise it commenced to rain, and it rained hard. Towards noon the Katcinas dressed up, putting on their masks, went out, crossed the mesa, came to the fields south of the mesa, and there they beheld large fields of corn, patches filled with melons, watermelons, and squashes. Everything was growing beautifully.

Having looked around a little while they turned around, taking with them a watermelon, an ear of fresh corn, and a melon. It was still raining so that their feet sank deep into the ground.

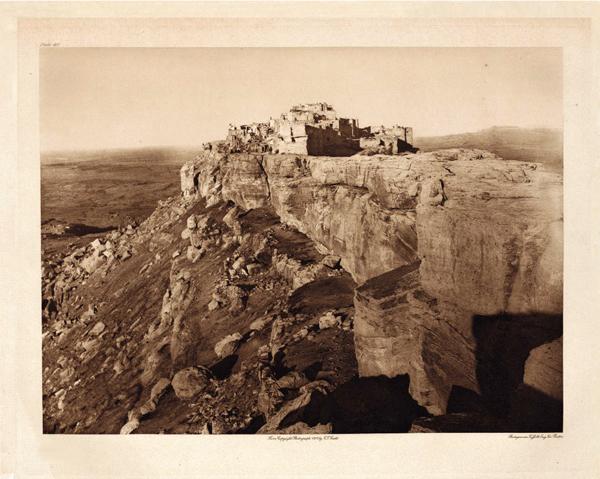

When they arrived close to the mesa somebody met them. It was Big- Skeleton (Wokómásauwuu), who owns the earth and the fields. He lived about halfway down the mesa near the mesa point. He told the Katcinas that they should go up the mesa and prepare a house there and live there, and from there they should perform their rites. So they went up on top of the mesa and have lived there ever since.

Soon after that the Wálpi also commenced to move up the mesa and build the new village, where it is at the present time situated.

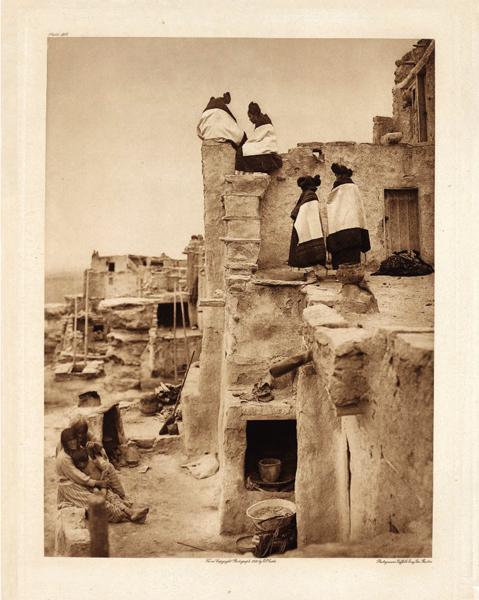

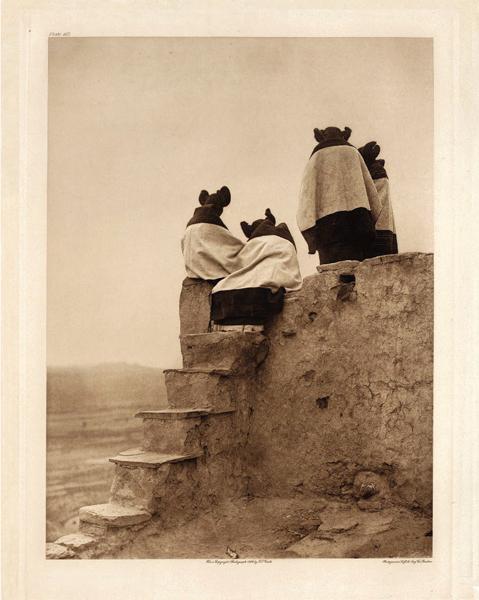

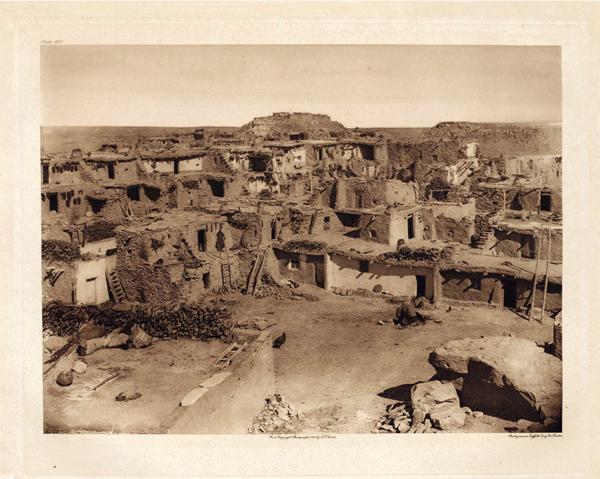

Photographs OF THE HOPI

The North American Indian by Edward S. Curtis is one of the most significant and controversial representations of traditional American Indian culture ever produced. Issued in a limited edition from 1907-1930, the publication continues to exert a major influence on the image of Indians in popular culture. Curtis said he wanted to document “the old time Indian, his dress, his ceremonies, his life and manners.” In over 2000 photogravure plates and narrative, Curtis portrayed the traditional customs and lifeways of eighty Indian tribes. The twenty volumes, each with an accompanying portfolio, are organized by tribes and culture areas encompassing the Great Plains, Great Basin, Plateau Region, Southwest, California, Pacific Northwest, and Alaska.

Featured here are a few of Curtis’s images of the Hopi from the Library of Congress collection. All images: Northwestern University Library, Edward S. Curtis’s ‘The North American Indian’: the Photographic Images, 2001.

To visit website:

http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/award98/ienhtml/curthome.html

Kachina Images

CLICK THE IMAGE TO VIEW GALLERY

You will note that in this painting Aholi is portrayed with a multi-colored head, the same as his cape. Evidently, this is how Aholi is known in the Third Message village of Oraibi where Earle lived for a year. In other villages on the three mesas, including Second Mesa where the Aholi in There’s Something in the Back Yard is said to come from, he is said to have a blue head.

U.S. History Images

The following are a few from the U.S. History Images site, an amazing resource for anyone interested in American history. All photographs: Hatzigeorgiou, Karen J. U.S. History Images, 2009.

To visit website:

http://ushistoryimages.com

CLICK THE IMAGE TO VIEW GALLERY

Songs of the Hopi

Sites of Interest

The North American Indian Photographs

All images: Northwestern University Library

http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/award98/ienhtml/curthome.html

Hopi Reservation Photographs

Karen J. Hatzigeorgiou, U.S. History Images, 2009

http://ushistoryimages.com